There’s a Charlie Munger story about the art of patient investing, that quality that’s easy to talk about but hard to preach, and Gautum Baid tells it well. Munger, 99, has read Barron’s Magazine for over 50 years. In that span, he’s found only one actionable idea, a cheaply valued auto parts company, which he bought at $1 per share and sold a few years later for $15. He earned about $80 million in profit on the investment.

Then he gave the $80 million to the value investor Li Lu, who turned it into more than $400 million. “I didn’t have a lot of ideas,” Munger said, “I didn’t find them easily, but I did pounce on one.”

The example illustrates a key tenant in Tom Lee’s investment process and Baid’s international bestseller, The Joys of Compounding, one of our favorite books. The value of true patience is hard to overstate in an investing landscape of tons of noise and very little signal. Quality investments don’t always come along, so the ability to sit, sit, and then pounce is a trait reserved to a select few. Extreme patience, deferred gratification, and the courage to act boldly all contributed to Munger’s enormous success, helping to make him a billionaire. As Munger says, it takes character to sit with cash and do nothing for months, sometimes years, until the right opportunities come knocking. In investing, you don’t get rewarded for activity.

In this Signal From Noise, we highlight this and other timeless lessons from Baid’s book, a master class in investing, mental models, frameworks, and enjoying the benefits of compounding in all areas of life. Baid is the fund manager and managing partner at Stellar Wealth Partners India Fund, an investment partnership modeled after the original Warren Buffett partnership fee structure. The Fund is based in the US and invests in listed Indian equities with a long-term, fundamental, and value-oriented approach.

Here are the highlights.

Delayed gratification

Munger, Warren Buffett, Joel Greenblatt, and other legendary investors like Peter Lynch didn’t build fortunes by panicking during recessions, selling out in 2008 or 2020, or making impulse investments based on a few negative headlines. No, they built fortunes partly because of an uncanny ability to ignore the noise, gloomy soundbites, and pundits. They compounded their wealth again and again, thanks to delayed gratification. As Baid explains, many great investors beat the benchmark S&P 500 over many years because they maintain a long-term view of several years, not weeks, months, or quarters. Great investors also tend to think like owners who buy a business, not merely a stock.

“If everything you do needs to work on a three-year time horizon, then you’re competing against a lot of people,” Jeff Bezos once said. “But if you’re willing to invest on a seven-year time horizon, you’re now competing against a fraction of those people.”

Baid highlights a famous Stanford University marshmallow experiment that gave 4- and 5-year-olds a difficult choice: Eat one marshmallow immediately, or wait 15 minutes and be rewarded with two marshmallows. It tests time preferences. High-time preference students want the marshmallow immediately because they naturally value the present more than the future.

After 40 years of data, the study found that the students who waited 15 minutes for both marshmallows registered higher SAT scores, lower levels of substance abuse, lower likelihood of obesity, better responses to stress, better social skills, and better scores on many other life measures.

The discipline of delayed gratification, Baid writes, builds up like a muscle. Rather than feeling a need to pile into a hot stock or make a quick profit next week, Baid illustrates the value in judging businesses, not stock prices. The stock price eventually reflects the underlying business, not vice versa. When management teams execute, the stock price often follows.

Take our popular Granny Shots portfolio, which has outperformed the benchmark S&P 500 by 74.1% since its inception in 2019. At any given point, especially during the 2022 bear market, you could point to smart-sounding reasons to sell many of the stocks in the portfolio. Last fall, many of the picks had fallen more than 20% at the market lows, including Apple, Microsoft, Tesla, and Nvidia. But delayed gratification and patience would have paid dividends for investors who held those positions, as the market has recovered quite substantially since October.

Investing checklists

Many top investors swear by checklists to keep them aligned with their principles. Regardless of the investment, they repeatedly return to a set list of questions. Baid asks himself four inverted questions before investing. He steals a page from Munger’s playbook, using inversion when looking for an investment. What are the reasons not to buy the stock? Baid always asks:

- How can I lose money on this investment?

- What is the stock not worth?

- What can go wrong with the perceived growth drivers?

- What’s the market’s implied growth rate of the stock’s current valuation vs. my own future growth rate assumption?

Similarly, Baid is always questioning himself and his investments. Where could I be wrong? What facts might I be missing? What are my potential blindspots? Quality investors know they need to change their opinions if necessitated by the facts. They don’t just hope they’re right. They evaluate the situation from a birds-eye view, looking for where they could be wrong. Then they change their minds accordingly.

Sometimes, less is more

Today’s marketplace is about clicks, eyeballs, the next big stock, consumerism, and options. The possibilities are endless. But Baid cautions against over-saturation and complexity. He teaches the art of simplicity, from how you invest to how you receive investment research to how many positions you have in your portfolio. A peace of mind is linked to simplicity that might even border on minimalism.

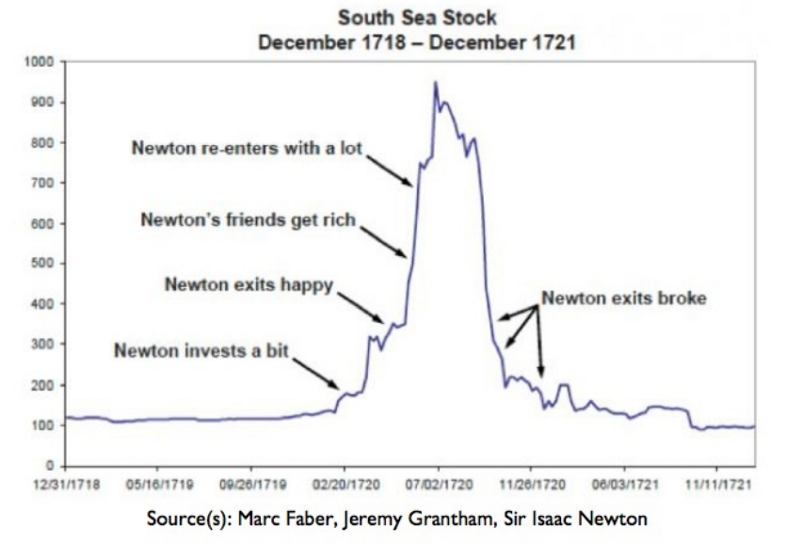

Gautam says true wealth is measured in terms of personal liberty and freedom, not monetary currency or money. He also knows true wealth means resisting the fear of missing out, a feeling humans have felt for at least hundreds of years, as Baid illustrates with the Isaac Newton classic example of FOMO during London’s roaring stock market of 1720. Investors have made the same mistakes for hundreds of years, regardless of technological advances. Three hundred years later, investors repeated Newton’s mistakes during the highs and lows of the Covid-19 market in 2020 and 2021.

Reading and knowledge compound

Baid points out that many successful business leaders, inventors, and investors are self-educated. While degrees can help, they know their learning journey only began on graduation day. The power of reading can transform an investor because you can learn from the accumulated knowledge and information of peoples’ entire lives in just a few hours, right in your own hands, via a book. Tom Lee reads for hours daily, and Buffett has said he spends about 80% of his workday reading.

Whether it’s about businesses, trends, news, biographies, or ideas, reading compounds over the years. In time, you connect dots subconsciously. Ideas percolate. Many hours of reading that lead to even just one excellent investment decision could render the time spent well. Baid notes that it can be difficult to quantify the lifelong benefits of accumulating knowledge. One quality idea from a book could lead to a million-dollar investment idea.

“Develop into a lifelong self-learner through voracious reading; cultivate curiosity and strive to become a little wiser every day,” Munger has said. “In my whole life, I have known no wise people (over a broad subject matter area) who didn’t read all the time — none, zero. You’d be amazed at how much Warren reads–and at how much I read. My children laugh at me. They think I’m a book with a couple of legs sticking out.”

Fundamental truths

Baid lists several principles to consider in your investment journey:

- Analyze stocks as if you are a part owner in the business.

- Volatile price fluctuations are your friend, not your enemy. The ability to capitalize on swings, especially to the downside, is an enormous advantage.

- The three most important words in investing: “Margin of safety.”

- Think in terms of opportunity costs when evaluating new ideas. Keep a high hurdle rate for new investments.

- Think probabilistically, not deterministically. The future is uncertain, as Lee says.

- Understand the power of incentives.

- Invert, always invert. Avoid pain by asking: What could go wrong here?

- Use both the left and right sides of your brain when making decisions. Left: logic analysis, math. Right: Creativity, intuition.

- Learn from others throughout life.

- Engage in visual thinking to understand complex thinking and organize thoughts.

- Embrace the power of long-term compounding. All great things come from compound interest, including relationships, skills, health, and wealth.

Baid concludes with a riff on that very powerful idea of compounding, which Albert Einstein called “the eighth wonder of the world.” He wasn’t mincing words.

“It takes a long time to create anything valuable,” Baid writes. “Work hard every day, even without seeing any results in the short term. Keep doing it consistently for a long time without giving up. Enjoy the process and live life according to the inner scorecard. Do not compare yourself to others. Instead, always endeavor to become a better version of yourself compared to what you were the previous day.

“Anybody who is doing all of these things is most likely going to succeed in his or her pursuit in life,” Baid continues. “This is exactly what Buffett meant when he said, ‘Games are won by players who focus on the field, not the ones looking at the scoreboard.’ Mahatma Gandhi described compounding in all its glory when he said: ‘Your beliefs become your thoughts. Your thoughts become your words. Your words become your actions. Your actions become your habits. Your habits become your values. Your values become your destiny.’ It all starts with one small belief, one small thought, one small world, one small action, one small habit, one small value.”

That’s how compounding works, one step at a time.

Your feedback is welcome and appreciated. What do you want to see more of in this column? Let us know. We read everything our members send and make every effort to write back. Thank you.

Access our full Signal From Noise library here, including interviews with bestselling authors Morgan Housel and Robert Hagstrom, and recent deep dives on semiconductors and opportunities in the luxury market.