“Peace on earth, good will toward men.”

Regardless of your faith, at this time of year, it is customary to reflect on the past 12 months and hope for a better world in the year to come. In 2022, we saw more armed conflict in Myanmar that claimed 18,327 lives; continued unrest in Afghanistan (3,822 fatalities in 2022); a drug war in Mexico (7,200 lives this year); and a continuation of the Yemeni Civil War (6,550 lives lost in 2022) – among others around the globe. On the bright spot, we did see the tentative end this year of a civil war in Ethiopia between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front and the ruling government.

That good news was canceled out by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February. Fatality counts and economic costs are imprecise, but the U.S. military estimates 100,000 military casualties (killed or wounded) on the Ukrainian side, and a similar number on the Russian side. Outside observers also believe there have been a “significant” number of Ukrainian civilian fatalities – some estimates already exceed 10,000. This is to say nothing of the tens of millions of displaced Ukrainians due to the invasion.

But this is a season for hope.

In the spring of this year, many feared that Ukraine would quickly fall to the vaunted military might of Russia. Yet here we are in December 2022, and Ukraine is bloody, but unbowed. It is true that there remains much uncertainty about the conflict and Ukraine’s future, but for today, we will behave as if hope has borne fruit and Ukraine has won peace and kept its freedom.

So what follows? We know from history – both recent and ancient — that peace can be fragile and fleeting. Ukraine must be rebuilt to become prosperous, fair, and free. In this edition of Signal from Noise, we will discuss the challenges that must be overcome in order to achieve that. We will tie that into how investors might benefit alongside a rising Ukraine.

Economists and diplomats have been looking into what it would take to rebuild Ukraine for months. For example, in October 2022, the U.S. Secretaries of Transportation and Commerce signed agreements with their Ukrainian counterparts to study the best ways to help the country rebuild its heavily damaged energy and transportation infrastructure. Economists and historians started by looking at an obvious source for inspiration: the Marshall Plan.

The seeds of modern-day Europe

Spearheaded by Secretary of State George Marshall, the Marshall Plan (official name: European Recovery Program) was a recognition that existing U.S. efforts to help allied European countries recover from the devastation of World War II would be doomed to failure if Germany was not also restored to freedom, dignity, and prosperity. (It was also an acknowledgment of the mistakes of post-World War I, when punitive economic treatment of Germany significantly contributed to the rise of Nazi Germany and another catastrophic world war.) In Marshall’s view, economic stability and prosperity were prerequisites for democracy and political stability.

The plan began with grants to help Europe with its urgent immediate needs. Those sums were reduced over time and were replaced by guarantees, loans, and incentives to motivate American companies to do business with Europeans and enter into deals to provide them with materials, technology, and expertise.

Although it lasted only four years, the Marshall Plan is generally regarded as one of the greatest successes of U.S foreign and economic policy. The assistance was not particularly high in monetary terms or as a percentage of recipient GDP, but the timing of it and the way it was implemented helped to spark a recovery that, until then, had faltered.

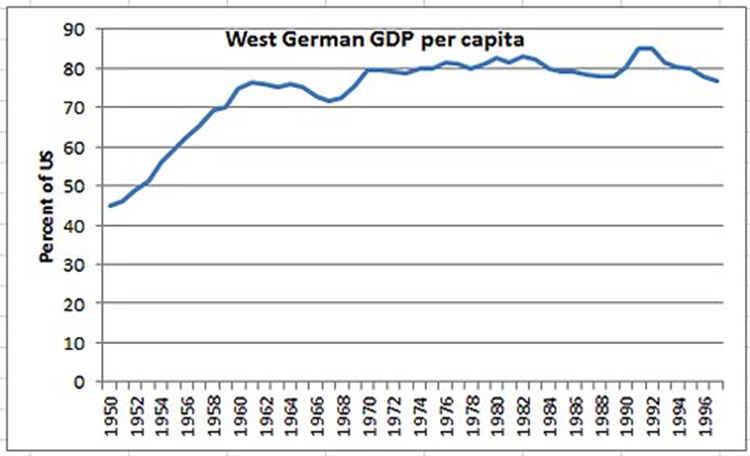

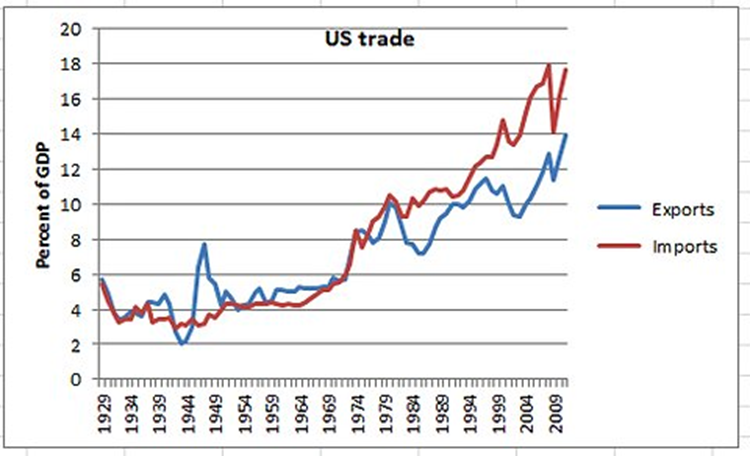

The United States benefited economically, too. It is no accident, for example, that Germany’s GDP per capita rose sharply in the decade or so after the Plan began. And it is also no accident that U.S. trade turned sharply upward in the years after that GDP-per-capita recovery.

The Marshall Plan did more than just greatly facilitate the recovery of many countries in Western Europe. It made it possible for those countries (including two former enemies) to turn into the prosperous and democratic allies they are today, laid the foundation for the creation of NATO, and helped to build Europe’s network of modern highways, railroads, and airports.

Twenty-five years after the plan was proposed, West Germany endowed a think tank at Harvard University called the German Marshall Fund (GMF), both in gratitude for the assistance and to ensure that the ideals of democracy, human rights, and the transatlantic alliance would continue. Recently, the GMF described the Marshall Plan like this:

“The Marshall Plan was not just an aid program; it responded to a geopolitical challenge in the spirit of enlightened self-interest. It did not just seek economic recovery but also democratic stabilization. It aimed to counter Soviet expansionism and combined aid with security guarantees in the newly founded NATO alliance.

The parallels to the modern-day situation with soon-to-be postwar Ukraine are obvious. Once again supporters are suggesting – not without reason, mind you – that helping to rebuild Ukraine is an act of enlightened self-interest, one that should strive for both economic recovery and democratic stabilization, particularly in light of expansionism from an Eastern European power.

Many here at FS Insight have pointed out that the current wave of inflation was ignited by Russia’s invasion, which immediately affected energy and grain commodities prices. To be sure, many other factors, from tight labor markets to supply-chain disruptions, laid the foundation for the current wave of inflation that the Federal Reserve has spent the past year trying to dampen. But as our Head of Global Portfolio Strategy Brian Rauscher puts it, “the inflation genie … was already trying to escape its bottle during the latter parts of 2021,” but it was the war that removed the proverbial stopper.

The differences are as important as the similarities

Yet, the GMF acknowledged that, although the Marshall Plan is an obvious source of inspiration for the recovery effort, “it cannot be a template for addressing the current challenge.” The Marshall Plan was an aid program funded by one major economic power – the United States – for the benefit of multiple foreign-aid recipients. As the program continued, many of the institutions needed to coordinate the requests, delivery, and distribution of the assistance were created as the need for them arose.

That is not the case today. A rebuilding Ukraine will be the only recipient of foreign aid, and it can expect to find many nations hoping to provide assistance – and to develop closer diplomatic and trading alliances. In addition to EU countries hoping to bring Ukraine into the fold of EU-flavored market-oriented democracies, the United States will certainly be motivated by both altruism and enlightened self-interest. So, too, will China and other economic powers, such as those in the Middle East.

And today, we have a multitude of international organizations that will each seek to have a say in the process—not only individual governments but also numerous IGOs and NGOs, with the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund leading a very long list.

What will Ukraine need?

Unfortunately, these numbers will continue to grow until the cessation of hostilities, and an ongoing war makes data collection difficult and dangerous. Nevertheless, we have some preliminary estimates from the government of Ukraine and from the Kyiv School of Economics.

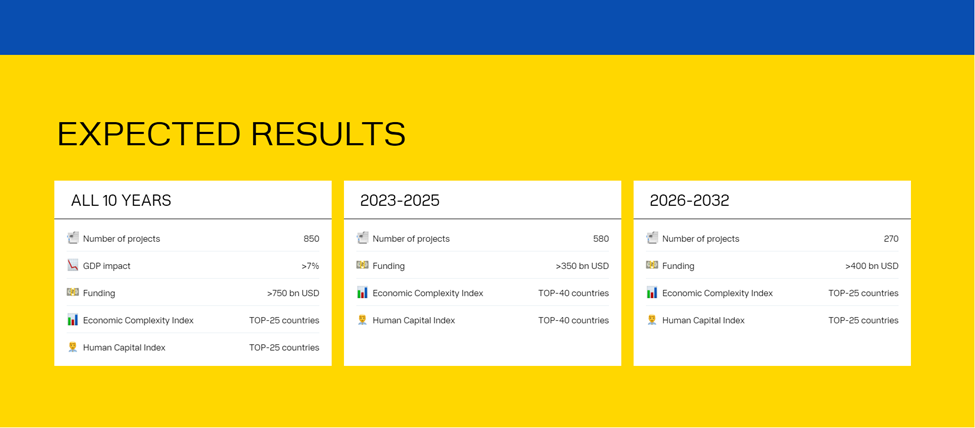

On July 4-5, 2022, Lugano, Switzerland, played host to the Ukraine Recovery Conference, with in-person attendance by many world leaders (and virtual attendance by Ukrainian officials). The Ukrainian government presented a dauntingly ambitious recovery plan – at least USD $750 billion spent over 10 years:

Infrastructure

The largest recovery need involves infrastructure, particularly housing. The Kyiv School of Economics estimated that the replacement cost for damaged or destroyed infrastructure as of September 2022 was in excess of $127 billion – and counting. Approximately $50.5 billion of those losses involved residential buildings, including nearly 120,000 houses and 15,600 apartment buildings. The KSE also reported that 978 medical facilities. 2,056 educational facilities, and 80 religious buildings have damaged due to the war. The Russian invasion has also caused $35.3 billion in damages through the destruction of roads and railways.

The Ukrainian government estimates that rebuilding the country’s housing and regional infrastructure will cost between $150 billion and $250 billion. Its plan includes restoration of water-supply, wastewater, and sewage networks (and building new networks wherever warranted), restoration of energy generation and distribution infrastructure, widespread modernization of heating and cooling systems, construction of waste management facilities, construction of interim and permanent housing for displaced Ukrainians, and creating the supply chains needed to run and maintain the infrastructure.

Logistics “De-Bottleneck” and Integration with EU

Ukraine’s historic ties with Russia, including its past as part of the Soviet Union, mean that much of the country is built to work with Soviet and Russian designs. From household refrigerators that depend on Russian companies for parts to railroads that use rail gauges incompatible with the rest of Europe (making it difficult for trains to cross Ukraine’s western borders), it appears that the aftermath of the war will be marked as an opportunity to rebuild to modern, Western standards that enable closer ties with the EU.

The government was seeking funds to construct shipping and transportation infrastructure, such as air traffic-control systems (towers, radar, etc.), modern rail systems, shipbuilding yards, cargo terminals, and roadways. Also falling under this category were initiatives designed to expand and promote tourism, including projects to make Ukraine’s natural sights and national parks more tourist-accessible. The URC estimated this will require $120B-$160B over a 10-year period.

Energy Independence and the Green Deal

One reality made painfully obvious is how dependent many countries are on Russian energy supplies. Ukraine was no exception: Although it stopped buying Russian gas directly after 2015 (in response to a war in which Russia annexed Crimea), it has long imported gas from Europe – which basically means from Russia, but indirectly. Further, half of the country’s power infrastructure (as of this writing) has been decimated by the war, leaving many Ukrainians facing the country’s customary harsh winter with limited or no heat and electricity.

Restoring power and heat to the nation is an immediate and top priority. On December 13, 2022, an international coalition of donors met in Paris to pledge $1 billion in immediate assistance to help Ukraine survive the winter. Much of the assistance will take the form of equipment and materials, from generators and power transformers to energy-saving light bulbs (it was estimated that 50 million LED light bulbs could reduce the country’s current power shortfall by 40%) and building supplies. But these are stopgap measures.

Ukraine, borrowing a phrase introduced by President Biden, has said that after the war it wants to “build back better,” and it estimates that this will cost about $130 billion. The list of peacetime projects encompasses the entirety of the country’s electricity infrastructure from power plants to residential distribution; improvements and expansions in capacity for hydro-based, biofuel, natural gas, and nuclear capacity (including development of natural gas fields and uranium mines), and improvements in oil-refining capacity.

Other Challenges

Before any rebuilding and recovery can begin, Ukraine will have to deal with the fact that for many months, the country was a battlefield – one that has millions of defensive landmines scattered around it. And those landmines will need to be removed – slowly and carefully (though there are some machines that now make the process a bit safer and faster). There is a saying that one year of mining requires 10 years of de-mining. To give an idea of how difficult it is to completely de-mine a territory, consider that in June 2022, workers in Howell, New Jersey discovered a Civil War-era landmine while preparing a site for new construction. (It was safely detonated.)

It is highly likely that the war will have exacerbated corruption in Ukraine—it almost always does. But it must be acknowledged that even before the conflict, Ukraine had a reputation for corruption and poor governance: In 2021, Ukraine ranked 122 out of 180 countries assessed by Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, with a score of 32/100 (higher is better).

Even if corruption within the government could be eradicated, its peacetime competence and ability to direct resources and manage a recovery would still be in question. As Yuriy Gorodnichenko, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley, put it: “There is this idealistic view that the government can direct resources and people will listen. As somebody who grew up in Ukraine, that’s not how it works.”

Another problem Ukraine will face is one that existed before the invasion, but might have been exacerbated by the war: a shrinking population. In the 10 years after its 1991 independence after the Soviet Union dissolved, the country lost 6.8% of its population to emigration. Although Ukraine ceased conducting censuses after that, experts estimated that as of February 2022 before the invasion, approximately 37.5 million were living in government-controlled Ukraine (not counting an estimated 7.9 million living in Ukrainian territories controlled by Russia before the war.) If accurate, this would mean that even including people in Russian-controlled Ukrainian territories, the country had lost nearly 16% of its population since 1991.

The war drove millions of additional Ukrainians into exile, and it is uncertain how many of them will return even after peace is won. In fairness, it is also possible that Ukrainian expats, moved by patriotism, will return in greater numbers to help rebuild after the war. This problem is exacerbated by a life expectancy that is one of the lowest in Europe (66.1 years for men, 76.22 years for women), thanks in part to heavy smoking and alcohol abuse.

These problems will hurt the people of Ukraine. They also pose significant risks to companies seeking to do business in the country—and to investors hoping to help and benefit from the country’s recovery.

The private sector will play a pivotal role in rebuilding and recovery, and Ukraine itself is already looking ahead. On September 6, 2022, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy (remotely) rang the opening bell of the NYSE, part of a PR push for private investment from abroad. “We are free. We are strong. We are open for business,” he said as traders and NYSE employees cheered.

We agree with President Zelenskiy on the important role the private sector will play in rebuilding Ukraine, helping the Ukrainian people recover, and helping the country become a prosperous, free-market democracy. Doing so is, as Secretary of State George Marshall asserted 75 years ago, an act of enlightened self-interest.

As we look at what Ukraine will need to achieve this, we can identify some of the companies that are well positioned to play a role – and profit – while helping Ukraine and its allies rebuild.

Opportunities Through Recovery

Xylem (XYL -0.11% ).

Xylem has expertise in many types of the infrastructural projects that Ukraine will need during its recovery, particularly as they relate water solutions in residential, commercial, agricultural, and municipal settings. This includes municipal water systems and sewage solutions, as well as agricultural irrigation solutions.

Jacobs Solutions (J 0.06% ).

Jacobs Solutions is a global engineering, construction, and consulting firm with highly regarded expertise in designing and building many of the types of infrastructure projects Ukraine will need. This includes work on power grids, telecommunications systems, and healthcare facilities–as well as military and security infrastructure. Jacobs’ attention to green projects and processes also synchronizes well with Ukraine’s stated postwar goals. The company, which already had operations in Ukraine before the war, has achieved strong revenue growth over the past three years. Jacobs is also well positioned to take advantage of the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act signed in November 2021.

Lockheed Martin (LMT 0.81% ).

As part of its efforts to support the war effort, the United States sent 5,500 Javelin anti-tank missiles to Ukraine—as much as two thirds of the existing U.S. supply, which will need to be replaced. The Javelin was also part of other countries’ assistance. The Lockheed-made missiles have proven so effective that many Ukrainians have started to refer to them as “Saint Javelin, Protector of Ukraine.” Meanwhile, in the wake of this latest example of Russian aggression, some countries in Europe have begun eyeing purchases of another Lockheed product, the F-35 fighter jet. LMT 0.81% has caught the eyes of many of us here. Mark Newton said on December 1, 2022 that technical indicators suggest that LMT was “one of the best stocks in the aerospace and defense subsector.” The company is also well regarded by Adam Gould as viewed through his quantitative lens, and Brian Rauscher has singled out the company as both “interesting” and “favorable.”

KBR (KBR 0.30% ).

Houston-based KBRis well-versed in engineering, construction, military logistics support and energy infrastructure. With operations in approximately 40 countries. It also has a robust portfolio of digital government services and sustainable energy technologies, both of which the Ukrainian government has identified as long-term priorities after the war is over.