“Quantum mechanics is counterintuitive. Its logic is very different from the logic we experience in our everyday life.” – Michel Devoret, Nobel Laureate in Physics 2025

As recently as November 2024, the practical deployment of quantum computing was widely viewed as a pipe dream – feasible, but nothing to bet on. Around that time, IDC quantum-computing analyst Heather West told the Wall Street Journal that a full-scale error-corrected quantum computer was still a decade away. Nvidia’s Jensen Huang was similarly skeptical – in fact, at the 2025 Consumer Electronics Show, Huang said that even an estimate of 15 years for useful quantum computers would be aggressive, suggesting that “a whole bunch of us would believe” an estimated timeframe of 20 years. Huang’s remarks caused a number of quantum-computing stocks to plummet that day.

To his credit, Huang followed that up two months later with a speech in which he wryly announced, “This is the first event in history where a company CEO invites all of the guests to explain why he was wrong.” We’re pretty sure there had been other CEO mea culpas before that but, nevertheless, Nvidia then announced that it would team up with Harvard and MIT to open the Nvidia Accelerated Quantum Research Center in Boston. The company has gone on to expand its involvement, investing in three major startups – among them Quantinuum ($600 million), PsiQuantum ($1 billion), and QuEra Computing ($230 million).

Nvidia is not the only legacy Big Tech company seeking to get a foothold in this field. As we will discuss later, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and IBM are each making substantive investments in quantum-computing research, and in recent months, each has reported important advances as a result.

Overlaying all of this is the increasing recognition by governments around the world that it’s not enough to win “just” the AI race, but that quantum computing has the potential to be just as strategically important, for different reasons. The United Kingdom is in the initial stages of its GBP 2.5 billion ($3.4 billion) 10-year quantum strategy, the Australian government has a AUD 620 million ($415 million) stake in the U.S. startup PsiQuantum (see below), and last July India’s government began inviting proposals for its INR 60 billion ($740 million) National Quantum Mission. Japan has committed JPY 1.05 trillion ($7.4 billion) to fund quantum-computing research from 2025-2030, while last April, Spain launched its National Quantum Technologies Strategy with a EUR 808 million commitment. This is separate from the estimated EUR 11 billion ($12.8 billion) that the EU as a group has committed through various initiatives.

Quantum computing research is unsurprisingly a priority for China, perhaps most visibly evidenced by Beijing’s $138 billion (CNY 1 trillion) Chinese government-backed venture fund supporting emerging technologies. Indeed, China likely accounts for the majority of global public investment in quantum computing research, more than all other countries combined, though the usual caveat is that China’s fiscal and budgetary decisions tend to be opaque so estimates can vary.

And then, of course, there’s the U.S. The bipartisan National Quantum Initiative Reauthorization Act, co-sponsored just this week (Jan. 8, 2026 to be precise) by Sens. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.) and Todd Young (R-Ind.), calls for an additional $2.5 billion in funding for quantum-computing research, adding to the $1.2 billion allocated in 2018 by the original National Quantum Initiative Act. (The pending legislation would also extend the timeframe beyond its original 2029 expiration date to 2034.) This is separate from other quantum and quantum-related initiatives by the Department of Energy, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), and the National Science Foundation, by state and local governments (Chicago, for instance), and those funded through the Commerce Department’s CHIPS and Science Act.

In Part I of this series, we will provide a brief overview of why quantum computing matters, the challenges facing researchers, and one route that companies are taking in their efforts to build a widely practical quantum computer. Part II will then cover other methodologies and examine some practical applications and related implications that might matter to investors.

First, a primer

As most likely know, traditional computers rely on binary mathematics. Every morsel of information is represented as a series of switches either turned on (with electricity flowing through it) – or not. Every process involves turning billions of these switches, embedded into transistors and chips, on and off. That’s true for whatever device you’re using to read this, it’s true for any of the servers in an AI hyperscaler, and it’s true for the computerized controls in your washing machine or car. Each on-off possibility is called a bit. For now, think of a bit like a coin lying on a table – it’s either showing heads or tails.

Quantum computers instead work in terms of qubits, using atomic and subatomic physics to manipulate atoms, ions, photons, or superconducting circuits to express a range of possibilities. Using our coin analogy, think of a qubit as a coin spinning on a tabletop. This isn’t quite a perfect analogy, but imagine if that spinning coin were considered to be simultaneously heads and tails, with the probabilities of each fluctuating constantly. This is a state known as “superposition”.

These qubits are then manipulated via “gates” (a specific physical process, for instance through calibrated microwave pulses or precisely applied laser beams) into a state of “entanglement,” so that what happens to any individual qubit influences the others. (Compare this to traditional bits, where the on-off state of one bit in and of itself does not influence the on-off state of another.) These qubit interactions cause waves of interference and amplification that correspond to probabilities of each of the numerous possibilities, and the most probable then can be identified and returned as the most likely “answer.”

This type of computing has enormous potential implications for tasks that traditionally have been thought of as time-consuming even for the fastest supercomputers. Examples of such tasks include infamous optimization problems – the fastest way to board passengers onto a commercial flight, or to route a fleet of commercial jets to hundreds of origins and destinations, for example. Scientists seeking to create new substances (medications, new materials for high-performance batteries or body armor, for instance) could hypothetically use quantum computing to quickly consider millions of possibilities in a relatively short time. It also has implications for investments and cybersecurity implications, which we will touch upon in part II.

For those uninterested in the underlying science, it might be enough to understand that classical computing excels at executing numerous tasks one at a time in sequence, quickly. Grasping how this differs from quantum computing can be mindbendingly non-intuitive.

Classical computing is a bit like reading a massive mathematics textbook, one word after another, sentence by sentence, from beginning to end. In contrast, quantum computing is a bit like somehow reading every word at the same time and using interference patterns to quickly learn what it most likely says about, hypothetically, proving Fermat’s Last Theorem. There will likely always be a need for the sequential processing capabilities of classical computing, but for certain types of tasks and problems, quantum computing offers the possibility of solutions to some types of problems in an almost infinitesimally tiny fraction of the time.

The challenges

As Dr. Devoret noted in the quote in the beginning, the laws of physics are very different when dealing with subatomic sizes in which quantum phenomena take place.

Experts in the field are currently working on different methods of generating qubits, but in each case, qubits are unstable and extremely sensitive. This means that even slight fluctuations in the operating environment – vibration, heat, and magnetic fields, for instance – can affect how qubit entanglement works and thus increase the likelihood of results that are suboptimally accurate – or just plain wrong. Furthermore, this makes manipulating or controlling qubits with accuracy and consistency – a necessary part of the computing process – extremely difficult.

How long a qubit maintains stability is known as coherence. It’s rare for qubits to last for more than a few seconds before collapsing, and some collapse in a few millionths of a second. The consistency and accuracy with which a gate manipulates qubits is known as fidelity. And because qubit calculations deal in manipulating probabilities rather than seeking certainty, some errors are inevitable. The phrase “fault tolerance” is used to describe a quantum system’s ability to continue operating correctly even when some of its qubits fail or introduce errors.

What all of this means is that regardless of approach, any institution striving to develop a practical quantum computer must strive to maximize qubit coherence, improve gate fidelity, and minimize fault tolerance by both minimizing the likelihood of errors and by detecting and correcting any errors that do emerge.

There are at least multiple pathways being explored in generating qubits for use in quantum computing, each with proponents among both established tech companies and startups. While a full technical explanation is beyond the scope of this note (and likely not of interest to our readers), suffice it to say that each presents a different set of advantages and also its own set of mindboggling engineering challenges to achieve the objectives we just mentioned, all while seeking scalability, minimal operating cost, and commercial viability. Below, we explore some of the methods being used.

The super ones

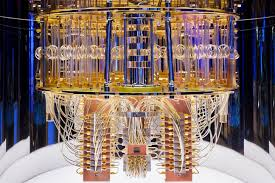

We begin with the “super” group. Note that we use the word super not to provide a qualitative assessment of merit. Rather, we’re referring to companies that are choosing to pursue quantum computing through the generation of superconducting circuits, supercooled to nearly absolute zero. This was the first approach hypothesized when the idea of quantum computing was first conceived.

It therefore seems fitting to start with IBM IBM -0.28% , arguably the grandaddy of corporate quantum-computing R&D (of all computing, really, despite some historical stumbles in terms of business decisions). The maturity of IBM’s program can be seen in the extraordinary level of detail in its ambitious quantum roadmap, which calls for a large-scale, fully fault-tolerant quantum computer (the holy grail for scientists in this field) by 2029. The company even has a name already for this as-yet-non-existent computer: Quantum Starling.

In 2025, IBM used its Heron quantum processor that featured advances in error reduction. (IBM, like all its competitors, has yet to achieve a fully fault-tolerant quantum computing system.) In keeping with the company’s stated pragmatic focus, IBM partnered with companies in other industries like finance (we’ll talk about this in Part II), automotive, transportation, and logistics to test the processor’s capabilities in real-world applications, with generally optimistically promising but inconclusive results.

It has since released Nighthawk, a quantum processor that more effectively links qubits together for significantly greater complexity and boasts improved coherence (nearly double that of Heron). In 2026, IBM hopes to release its next iteration, dubbed Kookaburra. There are three objectives for Kookaburra: improved fault tolerance, the ability to link multiple Kookaburra processors together, and the incorporation of quantum memory.

All of these are built on the concept of using supercooled superconducting circuits to generate qubits, which are then manipulated and read with precisely timed microwave photon pulses.

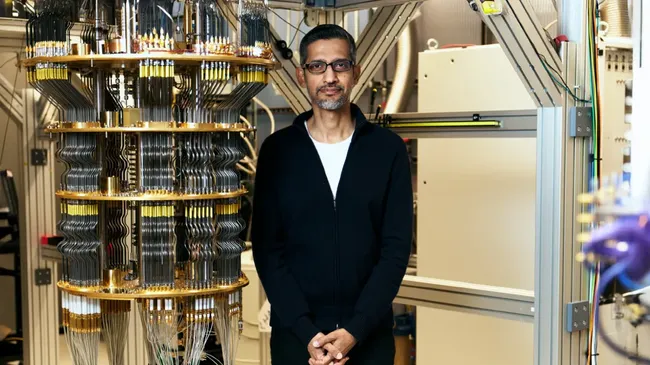

A competitor taking a similar approach (supercooled superconducting circuits) is Google GOOGL 4.16% . Though it entered the contest after IBM, Google can boast that it was the first company to demonstrate “quantum supremacy” – that is, to create a quantum computer that performed a task in a way that was superior to what a classical computer could achieve. It achieved this feat in 2019, but today perhaps the most visible showcase of Google’s efforts in quantum computing is its Willow quantum chip.

In December 2024, Google engineers announced that their Willow chip, incorporating 105 qubits in a square lattice, had run a verifiable benchmarking algorithm in five minutes. The same algorithm would have taken an estimated 10 septillion (that’s a one with 24 zeros following it) years on the classical Frontier supercomputer, then the fastest in the world. (It’s now No. 2.) For reference, 10 septillion years is an estimated 2.5 quintillion times the total age of our planet.

But that’s just a benchmarking algorithm, a bit like watching someone doing hundreds of pushups. Sure, that’s impressive, but you don’t tend to see athletes or everyday people doing pushups outside of a training context. However, last October, Google followed that up by running the so-called “Quantum Echo” algorithm, showing that Willow could simulate a nuclear magnetic resonance experiment 13,000 times faster than a classical supercomputer. That’s a practical task: Nuclear magnetic resonance is used to learn more about the internal molecular structure of a substance.

Perhaps the more notable achievement of Willow was the discovery that Google’s approach has the potential to drastically reduce computing errors. The team found a negative correlation between error rates and the number of qubits arrayed in its grid or lattice – more qubits led to fewer errors, and not by a little bit, but exponentially.

Fun fact: Michel Devoret, quoted at the beginning of this piece, is Chief Scientist for Quantum Hardware at Google.

A pure-play company in the quantum computing space focused on supercooled superconducting circuits is Rigetti RGTI -5.45% . Rigetti differs from IBM in that it has focused from the start on denser qubit connectivity, which enables faster gate speeds.

Rigetti also differs from IBM in two pragmatic ways. Firstly, it operates its own quantum fab, which helps them move more quickly on manufacturing experimental hardware for testing.

Secondly, Rigetti derives revenue from sales of on-premises quantum computing, while IBM’s quantum-related revenues are driven solely by sales of cloud-based access. There’s a certain symmetry to the difference between IBM and Rigetti in this respect. IBM’s approach to quantum computing echoes its decades-old focus on mainframe computing (and historic neglect of personal computing.) Rigetti, on the other hand, is employing a business model that is arguably more akin to the PC.

Yet another in the space is D-Wave QBTS -6.37% . Although it shares the supercooled superconductive approach with others, its primary differentiator is in how it proposes to use qubits to solve problems. Rather than adding energy via gates to manipulate a system of qubits and assessing the results while the system is in its energized state, D-Wave proposes performing calculations by gradually and precisely settling the system back down – a process called “annealing,” and using the resulting configuration to determine the most likely solution.

The quantum annealing approach enables far higher numbers of qubits – more powerful in some ways, but less flexible. Perhaps more importantly, there’s a case to be made that quantum annealing is inherently vulnerable to noise and analog control errors, and implementing effective error correction for quantum annealers is significantly harder than for gate‑model systems. Interestingly in light of that last vulnerability, D-Wave just announced (Jan. 7) the acquisition of Quantum Circuits, a company known for its gate-model error-correction technology. Quantum Circuits’ technology is being viewed as a way to add product diversification alongside D-Wave’s quantum annealing approach.

A final company deserves mention here, and it’s once again a familiar name: Amazon AMZN 2.06% . Amazon on Feb. 27, 2025 announced Ocelot, a chip developed in collaboration with Caltech with a name undoubtedly chosen because the company has applied a twist to the standard superconducting qubit, known as a cat qubit.

The cat qubit was named, as those who have taken an intro course to quantum physics must have guessed, for the hypothetical feline pet of Erwin Schrödinger, who (the cat, not Schrödinger!) was in a box simultaneously alive and dead at the same time. That’s actually a property that’s more or less true for all types of qubits, not just the cat qubit.

Where the cat qubit differentiates itself, for practical purposes, is its ability to strongly suppress what is known as “bit flip” errors automatically. If we return to our coin analogy, imagine that you flipped a coin, and it landed on the table coming up as heads. Now someone pounds on the table with a lot of force and it flips to tails. That’s a bit-flip error in a nutshell.

Because a common way to deal with quantum-computing errors is to build in numerous layers of redundancy in qubits, such an error-suppression feature could thus potentially result in the need for far fewer qubits (Amazon claims a 90% reduction.) In other words, this could lead to significantly smaller, far more power-efficient systems. (Other companies working with cat qubits include the French startup Alice & Bob, arguably the originator of the cat qubit proposal, and Finland’s privately held IQM Quantum Computers.)

Of course there’s a catch, and it’s this: while the use of cat qubits are unlikely to result in bit flip errors, another type of error known as phase flips becomes potentially twice as likely. This means that this approach poses a decision: Is it better to constantly need to deal with two types of problems, or is it better to only have to worry about one thing, but far more frequently?

Intermission

If there’s one thing we hope readers take away from this, it’s a better sense of just how experimental quantum computing technology really is. It’s one thing to merely hear a pundit give lip service to this assertion and another to take a deeper dive into why this non-intuitive field presents such technology hurdles.

There was a bit of a “Quantum Gold Rush” in pure-play quantum-computing stocks in 2025. For example, D-Wave shares notched gains of around 211%, while Rigetti advanced a healthy 45%. The experimental nature of advanced quantum computing is, however, similar to investing in a small pharmaceutical company that has a promising cancer-treatment candidate – in Phase I trials. The potential rewards seem significant if everything goes according to plan, but as is often the case, “that’s a big if.”

[In Part II, Signal From Noise will examine other approaches being taken in the attempt to achieve a widescale, widely practical fault-tolerant quantum computer, in the context of the companies involved. We will also take an investment-centric look at quantum-computing implications for finance and cybersecurity.]

As always, Signal From Noise should not be used as a source of investment recommendations but rather ideas for further investigation. We encourage you to explore our full Signal From Noise library, which includes deep dives on the race to onshore chip fabrication, the AI Merry-Go-Round, space-exploration investments, the military drone industry, the presidential effect on markets, ChatGPT’s challenge to Google Search, and the rising wealth of women. You’ll also find a recent update on AI focusing on sovereign AI and AI agents, the TikTok demographic, and the tech-powered utilities trade.