We are in the midst of “Dry January” – a month in which many (try to) abstain from alcoholic beverages to reset and recover from holiday excesses and/or set off on a road toward a healthier lifestyle. As readers of First to Market know, late 2024 social media mentions of #dryjanuary suggest that this year, climbing on the wagon will become more popular than ever. It’s too early to know whether participation this year will be boosted by U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy’s recent, widely publicized call for labels warning that even modest alcoholic-beverage consumption is linked to increased risks of cancer.

Yet Dry January likely does not worry makers of alcoholic beverages significantly. After all, it’s hard to kick any habit, especially addictive ones. Survey data suggests that the average American lasts just 10 days into January before returning to their imbibing ways – one in 10 barely make it to Jan. 3. That means that by the time you read this, a significant portion of participants have already returned to enjoying at least an occasional tipple. Last year, just 25% of Americans who attempted to stay dry in January succeeded. (No judgment here, by the way.)

That’s not to say that the alcoholic beverage industry is free from worries. Around the world, people are generally drinking less. An OECD study showed a decline in alcohol consumption in 23 out of 38 member countries from 2011 to 2021, with per capita annual consumption for adults (defined as 15 or older) declining from the equivalent of 8.9 liters of pure alcohol in 2011 down to 8.6 liters of pure alcohol in 2021. (For reference, assuming wine has 15% alcohol by volume, that translates to 76.4 bottles of wine in 2021, down from 79.1 bottles in 2011.)

If demographics are indeed destiny, as Fundstrat Head of Research Tom Lee is fond of saying, then it makes sense for companies like AB InBev, Diageo, Constellation, and Brown-Forman to be worried about surveys suggesting that alcohol consumption is declining amongst younger generations. Gallup survey data suggests that the proportion of young adults (aged 35 and younger) who drink fell to 62% in 2021-2023, down from 72% two decades earlier. Of those young adults who drink, some surveys suggest that fewer are drinking on a regular basis. Much of that appears linked to concerns about healthm – even before Dr. Murthy’s call to link modest alcohol consumption to increased cancer risk. A Gallup poll suggests that rightly or wrongly, a growing percentage of young Americans views even moderate levels of drinking as unhealthy.

This demographic trend appears to transcend U.S. borders. Reports from around the world seem to point to younger generations shifting away from drinking alcohol. France’s proud winemakers note with alarm that domestic consumption of red wine has been sinking for decades (though much of this is admittedly attributed to a shift to alternatives such as cocktails or even – sacre bleu! – white wine.) Meanwhile Ireland, long associated with alcohol consumption, recently reported that per capita alcohol consumption is at its lowest level since 1987 (though the country is still far from being a nation of teetotalers – per capita annual consumption in 2023 came in at the equivalent of 9.96 liters of pure alcohol, the equivalent of about 88 bottles of wine per person per year, or about 1.2 glasses of wine a day).

Many companies in the industry have responded by hedging their bets, introducing low-alcohol or alcohol-free versions of their traditional offerings. LVMH recently acquired a stake in French Bloom, a maker of luxury (>$100) non-alcoholic champagne, while Heineken and Budweiser (AB InBev) sell no-alcohol versions of their namesake beers. And recently, a store specializing in locally produced zero-alcohol wines opened in arguably the most prestigious and hallowed wine region in the world – Bordeaux, France. Such bets appear to have potential: IWSR, a research firm tracking the global beverage alcohol industry, reported that sales of no-alcohol beer, wine, spirits and adjacent, grew 29% in 2023 and estimates a CAGR of 7% between 2023 and 2027. Yet does this really foreshadow the end of recreational drinking? Are consumers – particularly young adults – really drinking less?

Perhaps not.

For one thing, alcoholic beverages are part of the consumer discretionary sector, and consumption is strongly correlated with household income and with consumer confidence. Thus, lower levels of drinking among young consumers could be partly a function of their financial situation (which presumably and hopefully will improve as the economy improves and as they progress through their careers.)

This supposed demographic shift in drinking attitudes does not appear to have resulted in a structural decline in actual consumption. This can be seen when we look at the operating revenues of five largest publicly traded makers of alcoholic beverages (U.S. markets) over the past two decades: We do not see any noticeable decline in the past 20 years. If anything, at all five companies, we see a slight overall upward trend in operating revenue.

Anheuser-Busch InBev (BUD -0.32% )

(brands include Budweiser, Corona, Stella Artois, etc.)

Diageo (DGE 4.03% )

(brands include Johnnie Walker, Guinness, Smirnoff, Tanqueray, Hennessy, etc.)

Constellation Brands (STZ 1.14% )

(Corona, Modelo, Pacifico, etc.)

Molson Coors Beverage Company (TAP 3.12% )

(Coors, Miller, Blue Moon, Pilsner Urquell, etc.)

Brown-Forman (BF.B)

(Jack Daniel’s, Woodford Reserve, Korbel, etc.)

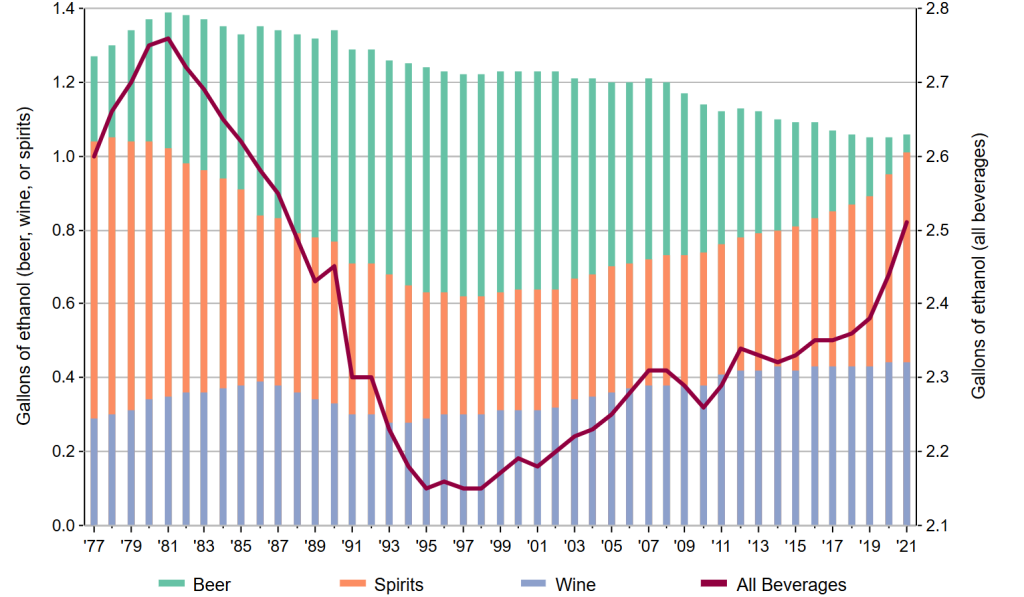

This is consistent with September 2024 data from the National Institutes of Health that shows that 172.9 million adults (aged 18 or older) had at least one alcoholic beverage in the past year – 67.1% of the adult population. The same report found that about 132.9 million American adults had at least one drink in the last month, about 51.6% of the adult population. American alcohol consumption peaked in the early 1980s and fell until the mid-1990s, when drinking arguably made a comeback in the U.S.

A study by Silicon Valley Bank on the state of the wine industry also suggests that reports about the declining popularity of alcohol in younger generations might be overstated. As the chart below suggests, the youngest cohort of consumers does not seem noticeably more likely to describe themselves as abstainers or infrequent drinkers.

Indeed, IWSR data suggests that while interest in no-alcohol equivalents is “particularly strong among younger legal age cohorts” including Millennials and Gen Z consumers, such customers tend to be what the research firm describes as “Substituters” rather than “Abstainers” – consumers who normally drink normal alcoholic beverages and turn to substitutes only under specific circumstances. This suggests that rather than taking market share away from alcoholic beverages, zero-alcohol equivalents could be increasing overall potential revenue for alcohol companies. It could also help explain why despite robust sustained sales growth in percentage terms, zero-alcohol beverages continue to make up only a small portion of the market, while alcohol consumption remains steady.

Social pressure to consume alcohol remains strong: an August 2024 study of drinkers in UK, US, Spain, Japan and Brazil, commissioned by Heineken, showed that pressure to eschew no-alcohol equivalents for the “real thing” remains strong. About 21% of Gen Z respondents admitted to concealing the fact they were drinking zero-alcohol beverages from their friends. Perhaps more tellingly, “when it comes to moderation, there is a gap in what people say versus what they do – 51% of people have ended up drinking alcohol when they said they wouldn’t, which could be due to social pressure.”

This suggests that all those surveys that show a shift in the attitudes of young adults regarding alcohol could suffer from social desirability bias, in which respondents provide an answer they believe is more socially acceptable rather than one that accurately reflects their views. This has long been acknowledged as a problem in surveys about alcohol consumption.

Current U.S. dietary guidelines suggest that men should limit alcohol consumption to no more than two drinks a day, and women should have no more than one drink a day. The current U.S. guidelines are roughly in line with those of many developed countries, though there is a growing trend toward guidelines that stress the importance of refraining from any alcohol consumption at least one day each week – as public-health authorities in countries like France, Germany, Ireland, and Japan advise.

It’s unclear whether Dr. Murthy’s views on a total abstention from alcohol will endure in the incoming Trump administration. However, President-elect Trump himself is well-known as a non-drinker; his pick to head up the Department of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has abstained for more than four decades; and his pick for Surgeon General, Dr. Janette Nesheiwat, has spoken publicly about the health risks associated with drinking. Regardless, given that the gradual increase in consumption in the past few decades has been accompanied by various public-health campaigns seeking to raise awareness of the risks associated with drinking, it is unclear whether any such warning would have a strong impact on sales of alcoholic beverages.

We encourage you to explore our full Signal From Noise library, which includes deep dives on investments related to natural disasters and an update to our overview of the semiconductor industry. You’ll also find discussions about weight loss-related investments, artificial intelligence, and the Millennial generation.