“Come fly with me, let’s fly, let’s fly away …” ~Frank Sinatra

At the February 2024 Singapore Airshow, COMAC (Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China) made a play to break into the global civil aviation market. The state-owned enterprise brought its C919 to the show, hoping its single-aisle, narrow-body airliner might take some market share from Boeing’s 737 Max and Airbus A320neo, the commercial workhorses used worldwide to ferry 150-190 passengers on short- and medium-haul flights (1-3 hours and 3-6 hours, respectively). COMAC also sells a smaller plane for short-haul regional flights, but the company is still in the design stages of developing a wide-body aircraft to carry passengers on long-haul and transoceanic flights.

Perhaps COMAC smelled an opportunity due to the rough times that have beset Boeing (BA 0.59% ) of late. As we were preparing this issue of Signal from Noise, The New York Times, citing an internal Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) slide presentation, reported that the plane maker failed 33 out of the 89 safety audits instigated by a January 5, 2024 incident in which a door panel blew off of a 737 Max 9 jet (Alaska Airlines Flight 1282) in midair. (A key Boeing supplier, Spirit AeroSystems (SPR), failed seven out of 13 similar audits, the newspaper reported.) The NYT story broke around the same time that Boeing 787-9 Dreamliner (LATAM Airlines Flight 800 from Sydney, Australia to Auckland, New Zealand) plunged midair without warning, injuring 50 passengers – reportedly after its instruments failed and the pilot temporarily lost control of the plane.

This year’s troubles emerged just as Boeing was recovering from the crashes of two 737 Max jets – Lion Air Flight 610 on October 29, 2018, and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 on March 10, 2019. These disasters led to all Max jets being temporarily grounded by aviation authorities around the world. Boeing was ultimately forced to pay $2.5 billion in monetary penalties (both civil and criminal) and damages to crash victims and their families to resolve the matter.

Boeing shares have lost more than a quarter of their value YTD, yet from a longer-term perspective, the company’s shares may well be considered resilient. Boeing continues to trade well above levels seen in early 2020, at the beginning of the global COVID pandemic, when they sank to as low as $95, and above levels seen during the 2022 bear market, when they fell to $118. Whatever weakness COMAC might perceive, some investors are not quite ready to write off Boeing.

Part of this has to do with the fact that Boeing does more than just make and sell commercial planes – although its unique status as a de facto U.S. maker of such aircraft is foundational to the company’s image and prospects. Boeing is also a defense contractor that manufactures military aircraft, missiles, satellites, drones, and spacecraft, and a provider of maintenance services to purchasers and lessors of its aircraft. Yet there is another reason to be sanguine about the prospects of the airliner giant.

To be sure, executives from several airlines have expressed unhappiness about the state of affairs at Boeing. In addition to justifiable concerns about the safety of Boeing jets, executives at longtime customers such as United Airlines, Southwest Airlines, and Alaska Airlines have also complained about the impact to their operating results and growth strategies stemming from limits placed on Boeing’s production capacity by the FAA for the duration of the civil and criminal investigations into the Alaska Airlines incident.

Yet it is American Airlines (AAL 4.18% ) that might show why some investors continue to have intermediate- and longer-term faith in Boeing. On March 4, 2024, American announced its biggest jet purchase ever, placing orders for 260 new narrow-body jets, including its first ever order for 85 of Boeing’s as-yet-unreleased 737 Max 10 narrow-body planes (as part of the Boeing order, American ‘upgauged’ 30 existing 737 MAX 8 orders to 737 MAX 10 aircraft). American is also ordering 85 Airbus A321 neos and 90 E175 planes from Embraer (ERJ). (Compared to the A321neo and 737, the E175 has a similar range but lower passenger capacity, intended for shorter routes in smaller markets.)

Some expect that Airbus (EADSY) will gain market share as Boeing struggles – it is already the largest commercial plane manufacturer in the world, having taken the top spot from Boeing in 2019. Nevertheless, the American Airlines order illustrates three important facts about the state of the industry that, in our opinion, currently work in Boeing’s favor during this challenging period for the company.

Growing Demand

According to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the global air transportation network has doubled in size at least once every 15 years since 1977, and the United Nations-affiliated group projects that this trend will continue.

Industry analysts expect significant growth in global demand for new commercial passenger and cargo jets for years, and even decades, to come. On the passenger side, this will be driven by corresponding growth in the demand for air travel, as incomes rise and the middle class expands in various economies, particularly in Asia.

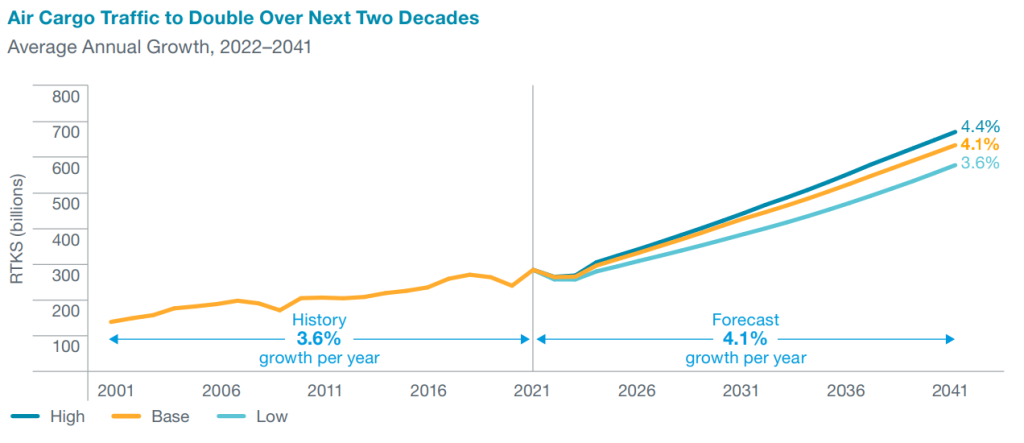

On the cargo side, growth in global trade is expected to drive increased demand for air freight transportation. In addition to demand for new air freighters, this could bump up demand for passenger planes, as air freight is often shipped on older passenger jets that have been retrofitted as cargo carriers. (Boeing also commands a 90% share of the market for purpose-built freighter jets.) Boeing’s own research suggests that air cargo shipping could double by 2041.

All of this is in addition to demand generated by the need for regular replacements as jets accumulate irremediable wear-and-tear and reach the end of their lifespans. Based on typical usage, a wide-body jet has an estimated lifespan of about 40 years. A narrow-body jet can last for 25-30 years before it can no longer be flown safely.

Still, carriers tend to replace passenger jets every 10 to 15 years, changing them out for newer models that are more technologically advanced and fuel-efficient. (Those older planes usually get repurposed as cargo jets or broken down for parts – either by the airline’s own fleet maintenance staff or by third-party companies who buy used aircraft and sell parts.)

Limited Production Capacity

For decades, the airliner industry has operated as a de facto duopoly. Any company seeking to purchase a large commercial airliner has had only two options:

Boeing (BA 0.59% ). Currently headquartered in Virginia, Boeing boasts a history going back to the earliest days of aviation. Its largest business segment is its Commercial Airplanes division, but the company is also major defense contractor, offering not just military aircraft (bombers, transports, and the Apache and Chinook helicopters), but also missiles and missile-defense systems, along space-exploration products (the company was one of the primary contractors for the International Space Station.) Boeing also has divisions dedicated to providing financing, aftermarket services, and support for its commercial aircraft.

Airbus (EADSY). Boeing’s primary competitor has its roots in a consortium of European aerospace companies that consolidated in 1970 to better compete with Boeing and other American aerospace companies such as Lockheed and McDonnell Douglas. Its predecessor companies include France’s Sud Aviation and the British Aircraft Corporation, perhaps best known for jointly developing the Concorde supersonic airliner. Airbus has since become the largest manufacturer of airliners in the world, as well as the largest maker of helicopters. In addition to airliners, Airbus also competes with Boeing in the defense sector, providing a range of military planes, helicopters, satellites, and spacecraft.

Although Boeing’s share of the airliner market has been steadily falling since the mid-1980s, both airline makers are at a point where they have far more business than they can fulfill right now. Long-standing backlogs, currently estimated at some 13 years between order and delivery, are a fact of life at both companies.

Source: CAPA – Centre for Aviation Fleet Database

Fleet stickiness

Although, in the broadest terms, the range of Airbus and Boeing commercial jet offerings includes models that are roughly analogous to each other in terms of passenger and fuel capacity, switching from one company’s planes to another is not simple. Pilots need to be trained and certified on each plane they are allowed to fly, and each company’s planes require separate teams of maintenance facilities, tools, and parts – and maintenance personnel trained and certified accordingly.

While some airlines find it beneficial to operate mixed fleets, with aircraft from both companies, shifting the balance from one to another is a complex decision rather than one that can be made on the fly (pun intended).

Effectively, this means that even if Boeing’s reputation has been dented, and even if Boeing’s ability to maximize production is temporarily impaired, its airline customers would not find it beneficial to impulsively abandon it for its only current competitor.

Barriers to entry

With the situation as described, it might be surprising to laypeople that COMAC is the only company currently looking to enter this industry. And yet, this is an industry with significant barriers to entry. Just ask Mitsubishi, which in 2007 announced plans to develop a new airliner for shorter regional flights. In 2015, the MRJ90 took its maiden test flight, but with multiple subsequent delays in final design and testing, the Japanese conglomerate canceled the project in February 2023, dissolving its Mitsubishi Aircraft Corporation subsidiary.

It can take anywhere from 10 to 15 years to bring a new commercial jet to market. This includes two to three years to conduct market research and feasibility studies, and develop conceptual designs. Add five to seven years of detailed design and engineering work (including plenty internal testing along the way), another three to five years to get FAA certification into design and manufacturing processes, and another few years to build and test actual prototypes, establish supply chains, and set up the manufacturing facilities and bring them online. Along the way, a company can conservatively expect to burn through $10 billion or more – and that’s assuming everything goes more or less smoothly.

COMAC began development on the C919 narrow-body passenger jet it brought to the Singapore Airshow this February back in 2008. A prototype was not completed until 2015; its first test flight took place two years later, and it was not until 2022 that COMAC delivered the first production plane to a customer (China Eastern Airlines). It is also worth noting that the 14-year development of the C919 likely benefited from espionage: at least one Chinese national, purportedly an intelligence officer, was convicted in 2022 for the theft of industrial secrets from U.S. aircraft-components manufacturers – information that several aviation trade publications report was used to assist in the development of the C919. It’s also important to note that, in the case of COMAC, the overall process did not involve the FAA or its European counterpart, the European Aviation Safety Agency.

When Boeing and Airbus develop new planes, they involve their respective home countries’ regulators throughout the engineering, manufacturing-design, and testing processes. This greatly shortens the airworthiness-certification process needed for planes to fly in other jurisdictions not covered by the FAA and the EASA.

All of this suggests that COMAC will not be in a position to provide plane-hungry airlines with a third viable alternative in the near future. Until it can, or until Airbus and Boeing expand their manufacturing capabilities, airlines will need to prioritize loving maintenance of their existing fleets.

Two companies that we believe might be positioned to assist in this endeavor are:

AAR Corp (AIR 0.50% ). AAR is a provider of maintenance, repair, and overhaul services for aircraft components including engines, avionics, instruments, hydraulics, landing gear, wheels, and brakes. The company’s product and service lines cover planes made by Boeing, Airbus, Embraer, and others. It also sells new and used parts for the maintenance of various aircraft and has a division specializing in transportation services for militaries and governments. AAR’s clients include major airlines and U.S. government departments and agencies, including branches of the U.S. military.

AerSale (ASLE 1.66% ). AerSale provides maintenance, repair, and overhaul services for a range of aircraft parts, including engines, landing gear, and other components. The company also sells used aircraft, as well as used parts, engines, and components. In addition, AerSale helps airlines manage their own inventory of spare parts. AerSale clients include major airlines and air cargo companies.

In closing, we should note that nothing in this piece should be viewed as an assessment of the plentiful and harsh criticism that has been leveled at Boeing in recent months. We have striven only to present some ideas about what that criticism might mean for shareholders and prospective investors interested in companies in the field of commercial aviation. As always, Signal From Noise should serve as a starting point for further research before making an investment, rather than as a source of stock recommendations.

We also encourage you to explore our full Signal From Noise library, which includes deep dives on topics such as artificial intelligence, our aging power grid, the path to automation, and infrastructure. Other past topics include opportunities associated with “vice” companies and the rise of Generation Z.