“When you play the game of thrones [chromes], you win, or you die [go bankrupt]. There is no middle ground.” – Cersei Lannister

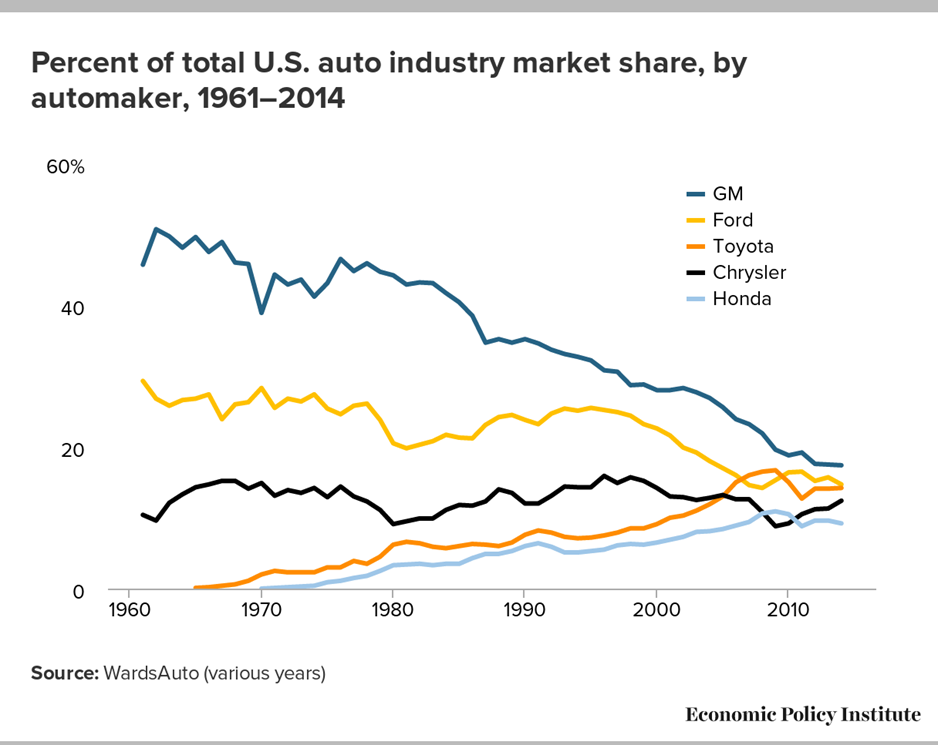

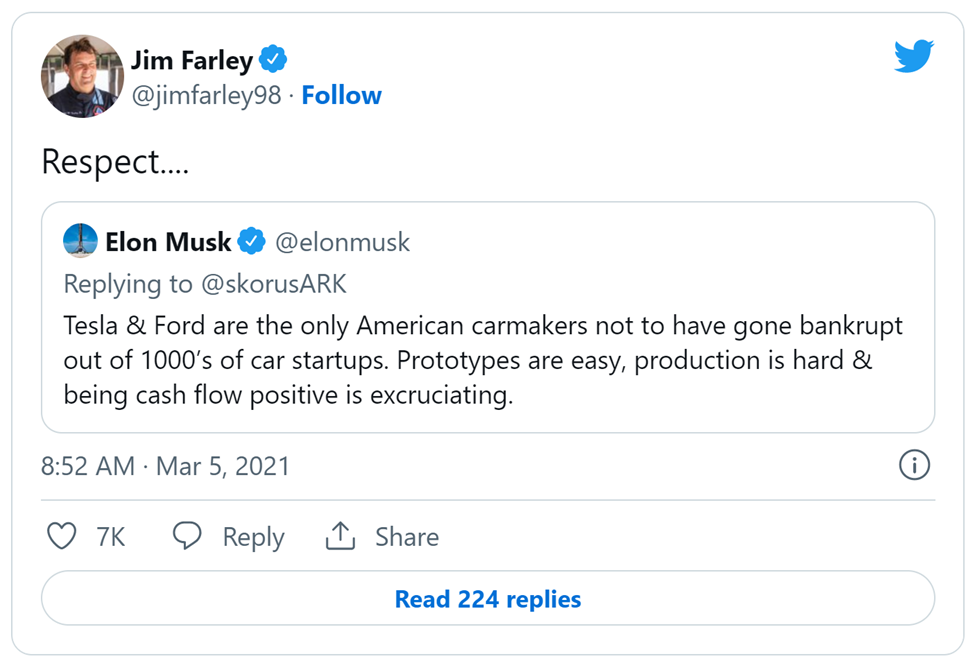

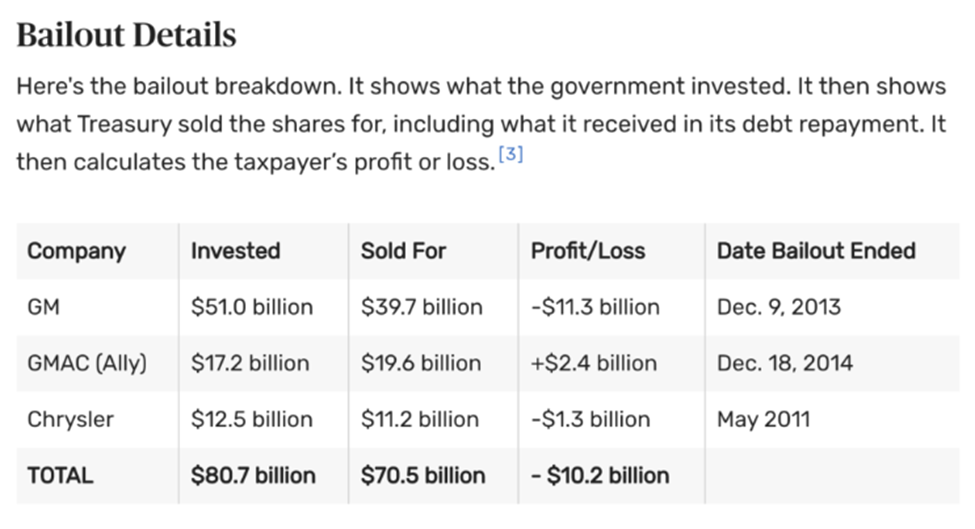

An intense quote from an intense show, obviously slightly adapted by our team. However, in a commercial sense, it captures the intense competition necessary to succeed in profitably selling automobiles. You can engineer a great vehicle and produce it by the tens or hundreds of thousands, but you also must also ensure consumers will buy it. Your competitors can quickly get the drop on you by understanding any of these three steps better than you. The rewards are high but often fleeting in the auto industry. One day you’re on top; the next day, you’re majority owned by Uncle Sam or the United Autoworkers (UAW). The auto industry is capital intensive, high-risk and subject to the fickle whims of both consumers and congressional committees. The barriers to entry are sky-high, and while we’ve called the airlines in this column as subject to “bankruptcy dodgeball,” in the auto industry it’s more like “solvency hunger games.” As you can see above, only two American companies have avoided this fate.

There’s always finger-pointing and Monday morning quarterbacking about reasons for spectacular failures and successes, but we believe that competent and forward-looking management with a capacity for execution over promises is what is truly key. While Detroit blamed its decline in the 70s and 80s on the United Autoworkers, the reality is that the Japanese devised superior methods of production (Lean Six Sigma) that rendered how much a plant worker got per hour a moot point. It would be like the legacies saying today that Tesla is ahead of them because of outstanding pensions; clearly, this is not the case. Not even Lee Iacocca’s immensely successful minivan could turn the tide. Also, Ford and GM’s efforts to expand international production into more accommodative labor markets were essentially an unmitigated disaster that left the stocks in no man’s land for the millennium’s first decade.

The companies are still paying for the deals and acquisitions for deals and acquisitions’ sake pioneered by Jack Welch and imitated by Detroit C-Suites. It didn’t work for Detroit, and it didn’t work for GE, either. We believe Welch’s corporate Frankenstein has to be taken out back and shot. A new scion of the industry proved that short-termism and pleasing Wall Street analysts could be thrown out for focusing on engineering and production over all else. He proved that short-termism is inferior to a solid plan and deliberate investment for the product rather than what the sell-side thought was best short-term. Tesla was initially hated by the Street and is now one of the world’s largest companies. Detroit follows their lead now, not the other way around. The market has spoken clearly about future prospects.

The decision to buy a car in America can be a loaded one. It’s about more than utility; it’s about identity, which adds another complex layer to the already infinitely complex process of automobile design and manufacturing. It’s gotten even more complicated with Electric Vehicles and Autonomous Driving, which will redefine one of the most significant inventions in history and have the potential to unlock the untapped economic potential on the scale of the first wave of industrial mobility. They have been a part of the American zeitgeist since soon after their inception. It is not a coincidence that much of early Rock N’ Roll, from Ike Turner’s Rocket 88 to Chuck Berry’s No Particular Place to Go and Maybellene revolve around automotive themes. It’s also no coincidence that the world’s largest company, which specializes in understanding consumer appetites and needs, sees a massive opportunity to break into the automobile industry with Silicon Valley’s worst kept secret, Project Titan. Let’s break down some key characteristics of the Auto Industry to get our discussion started:

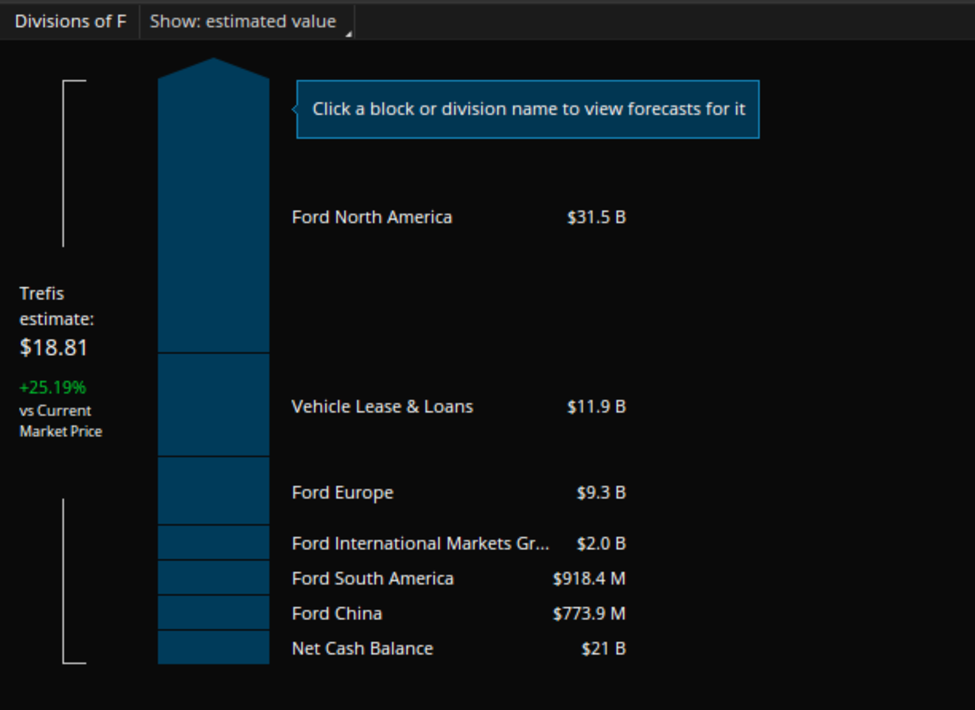

- The automotive industry is in the Consumer Discretionary sector and is considered highly cyclical, meaning that it is sensitive to economic activity and the health of the consumer balance sheet. Automobiles are considered a durable good. GM’s credit was spun off into Ally Bank whereas Ford Credit is still a very vital portion of the company accounting for a significant portion of total revenue.

- Legacy automakers are extremely sensitive to credit conditions since a lot of their sales are made possible by credit. This is partially why the auto bankruptcies followed the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, which was marked by anomalously high levels of credit default across loan products.

- The legacy US automakers have massive international manufacturing and logistics footprints. The industry is one where organized labor has an outsized impact and the United Autoworkers are known for negotiating well on behalf of their workers. Efforts to internationalize the labor force to countries with lower costs had mostly disappointing results, but the legacy of this ill-fated investments remains an albatross for some of these firms. They are still making efforts to optimize assets.

- The business of automobile production is highly capital intensive. Margins on vehicles are also thin relative to many other products. Therefore, commodity spikes, supply interruptions and logistics issues, and curtailment of capacity (which can reduce benefits of scale) can all eat into profitability quite quickly. These dynamics mean that fortunes can turn very abruptly in the automotive industry. Several times different legacy automakers gained a lead over their others and seemed supreme for a while. Almost always, ill-fated investments and corporate strategies burned the advantages.

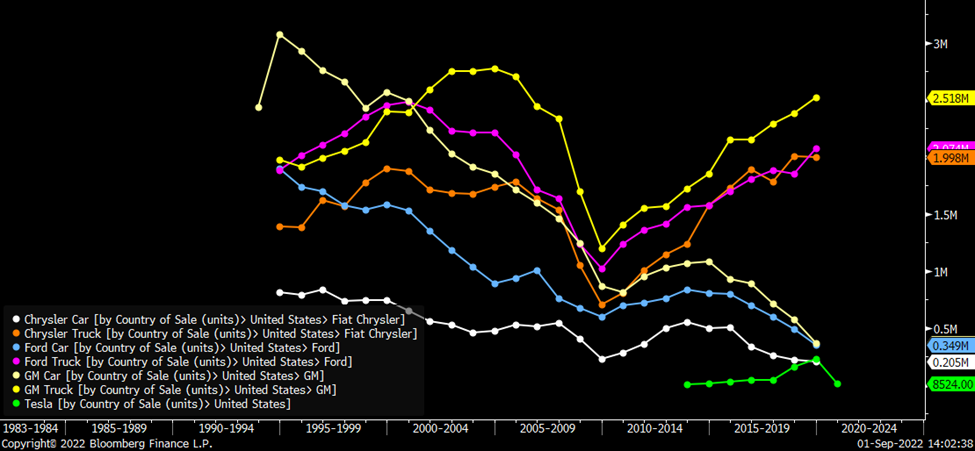

- The industry is being transformed by environmental concerns, new entrants, and government emissions regulations. The cash-cow of the American automakers, SUVs and trucks, have also been at the forefront of greenhouse emissions concerns. While the industry has chosen to focus on efficiency of emissions over the past years, they have largely abandoned passenger cars in favor of higher margin trucks. The general approach of the legacy automakers seems to be fund massive expansions into Battery Electric Vehicles (BEV) with the high margin trucks that consumers and investors both love. P/E ratios and other valuation metrics indicate a premium on companies who have the most developed and plausible plans for the transition to EV from their polluting gas-powered counterparts.

The automobile industry is one of the most enigmatic and storied in the history of the United States. Their wares reinvented society and unlocked untold economic potential from what was once a sleepy rural nation of primarily farmers. The growth of urban life and its economic centrality directly resulted from the automobile’s democratization. Detroit once represented the pinnacle of success, and too often, it now is a poster child for hubris compared to shiny new innovators. However, the reality is more complex than the binary arguments heavily promoted by the algorithms that determine our digital feeds. Understanding the potential future path of mobility requires correctly understanding the history of one of the most significant commercial revolutions in human history.

Lessons from “The Kings” of The Auto Industry’s Tumultuous Past

The competition in the auto industry is of mythical proportions. There are very few companies that have ever become as ingrained with the American national identity as the auto companies. The “arsenal of democracy” that enabled the Allies to vanquish the Axis was largely made possible by the auto companies. The Big Three reined as some of the most successful and iconic companies in American history.

They lost some ground to the Japanese but then gained market share by focusing on SUVs and light trucks. Their inability, or lack of willingness, to pivot from these successful high-margin vehicles culminated in two of the Big Three ending in high profile bankruptcy and government bailouts. Some of the management lessons from the epoch of the many rises and falls of the American auto industry are perennial lessons that also shed light on where the industry may be headed and who is best equipped to win the Game of Chromes and define the next chapter of mobility.

The Red Wedding: Be Careful Who You Partner With

The Red Wedding is an infamous scene from Game of Thrones where some of the most beloved characters are lured to a wedding and mercilessly slaughtered in a deceptive manner. It was one of the most memorable and impactful scenes in the history of HBO’s content. The fallout from the Auto industry’s “Red Wedding” took half a century to fully play out, and the actual event was quite pleasant by all accounts. What came decades later necessitates the comparison.

The groom was Henry Ford’s grandson, William Clay Ford and Martha Firestone (of Firestone tires.) Their marriage codified a close corporate relationship that had begun in 1896 between Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone. Firestone and Ford were close in commercial endeavors: the tire company supplied the bulk of Ford’s tires for the 20th century going back to the 1920s. Bill Ford Jr., the current chairman of Ford’s board, is a Firestone and a Ford. His grandparents were the ones that married that day.

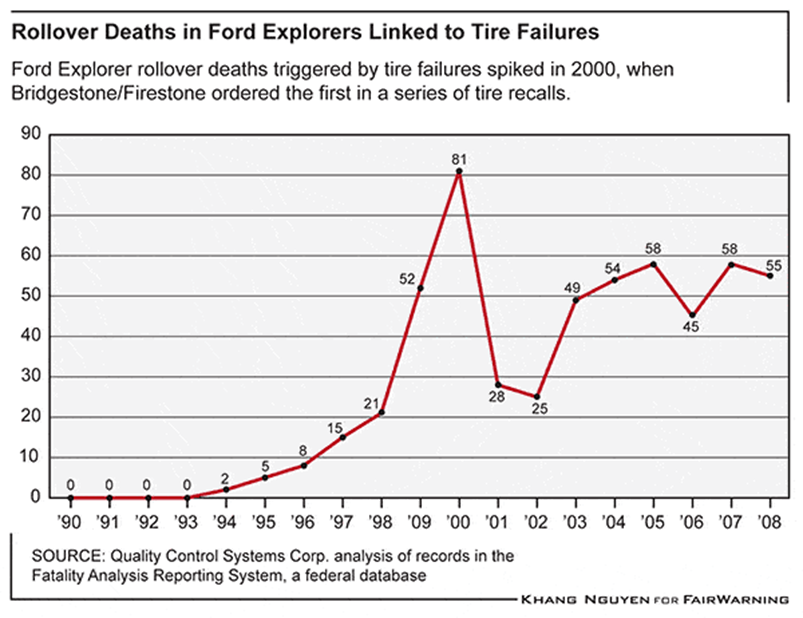

Ford had safety and quality issues in the past, but the nasty epoch that developed between the two dynasties was one of the darkest periods of the company’s history. Ford has had a lot of ups and downs over the years. In 2000, the company was doing well and was cash rich. However, the company was also producing a lot of cars at a loss and in terms of contribution to profitability, the firm was extremely concentrated. About 67% of profits were due to the incredibly successful Ford Explorer model. The company was so cash-rich that investors complained they had too much cash. This illustrates how fortunes can turn since only 8 years later the entire American auto industry was on the brink of insolvency and only Ford would survive.

However, it was discovered that the Firestone tires that were on many models of this heavily sold product were defective. They tended to disintegrate during hot weather with disastrous safety results. Firestone’s management behaved in a way that was outside Ford’s ethical boundaries and both companies devolved into a brutal corporate match of finger-pointing and even trying to get the government to investigate the other, an unprecedented level of acrimony in the auto industry.

As Douglas Brinkley noted in his grand history of Ford, Wheels For The World, “Once again, industry observers were shocked by the depths to which Ford and Firestone had sunk. No one could recollect another instance of one company asking the government group to go after another.” While Bill Ford Jr. was technically from both families, he chose Ford and left Firestone in the dust despite noting what a difficult personal decision it had been. It was not a difficult financial decision. The ultimate financial cost of the fiasco was $3 billion for Ford and the cost in lives was devastating at 271 souls lost.

The CEO Jac Nasser, known as “Jac the Knife” for his ruthless cost cutting had to go before congress and apologize and even let consumers know his family had three explorers in a contrite commercial. Insiders at Ford largely blamed “Jac the Knife’s” cutting for the debacle. As a technical specialist at Ford said, “They got rid of so many senior engineers and guys with test-operations experience. You knew it because the billboards at work were filled with retiree party announcements. Those older guys were the ones relied on to catch quality problems.” This brings us to our next lesson.

Plan For Succession Well and Keep The Nobles Happy: In Automobile Management, Sometimes Nice Guys Finish First, Sometimes They Finish Last

Ford and the Big Three of the American auto industry had a notoriously tough corporate culture, often characterized by a take-no-prisoners approach. When Bill Ford Jr. was being considered for the top spot after he made a name for himself at the Detroit Lions, many insiders of the proverbial court at Ford sneered at the prospect of his ascent. They said he was a nice guy, that he would get chewed up and that he was an idealist who would never make it in their business, dominated by tough guys like Lee Iacocca. However, Bill Ford Jr.’s consideration for his employees, even those far lowlier than him on the scale is ultimately what saved Ford from the unthinkable fate their peers suffered, being majority owned by the US government and the United Autoworkers. Apparently, the UAW and Ford employees were quite impressed with the fact that after a plant accident that injured workers, Bill Ford Jr. rushed to the site immediately to begin helping efforts to help the injured and clean up.

The UAW never forgot this magnanimous action and some insiders say it served as the foundation for a better relationship between Ford’s management and the UAW that would ultimately save the company in its darkest hour. While common consensus on Wall Street is that the UAW caused bankruptcies, according to Bill Ford Jr., it was a two-way street. Ford said on CNBC’s squawk box, “Over a many-year period, they [UAW] were asking for more, but we’re the ones who gave it. But then when we got into a really tough period, I sat down with Ron and I said, ‘Ron you have to help me save the Ford Motor company’ so we didn’t have to go through bankruptcy, so we didn’t have to get a Federal bailout and he did that.”

The key here is that the United Autoworkers, when the auto industry began to hemorrhage cash, began to gain more and more relative power. One of the only ways a flailing auto company can find savings fast is to renegotiate contracts with the unions in the shared interest of keeping the company solvent. The UAW is tough to negotiate with and their President Ron Gettelfinger was appropriately feared by the leadership of the Big Three. As the financial crisis raged, more and more, their fate was going into his hands.

The approach of other auto executives that tried to placate Wall Street and play hardball with the Unions ultimately resulted in their demise. The UAW did not cave to concessions from executives of companies like Delphi, a key GM supplier, that would set into motion the events that would lead to their demise and restructuring by Uncle Sam.

GM was the undisputed leader of the auto industry for many years, particularly in the post-War economic expansion that defined modern America. However, the culture became calcified, and it discouraged the type of innovative thinking that is necessary in difficult industries for survival. The old saying was “you go along to get along” at GM. Their product development had become too bureaucratic, and they had a lost a feel for the essential “sizzle factor” that can often drive consumer decision-making. Robert Wagoner rose through the ranks by not making a fuss and by “going along to get along.” He was a finance guy and took very little ownership of product development. He didn’t resist the bureaucratic culture of complacency where imagination failed. He didn’t necessarily understand the core of the business well enough, and the existential issues it faced, to demand the tough and innovative changes necessary to right the course.

He let the momentum of a calcified organization that was bleeding cash, missing targets, and filling up parking lots with unwanted inventory carry the day over sensible and urgent action. Like some other auto executives such as Nasser, he had the right idea on a few areas (Nasser’s early idea of integrating the internet into Ford’s business were prophetic but poorly executed), but didn’t have the leadership chops to turn the ocean liner around. Everyone liked him though. He was personable and most people liked him socially, but he definitely finished last. The US Government forced him to step down as a condition of restructuring and poor old Wagoner, nice as he was, has become the face of Detroit’s hubris and intransigence that ultimately led to the failure of two of the Big Three.

The Current State of Competition and What It Means For The Next Chapter of Mobility

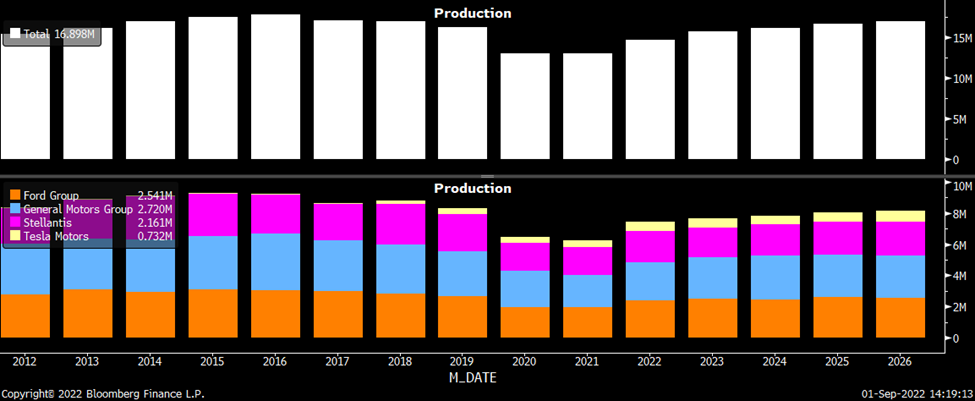

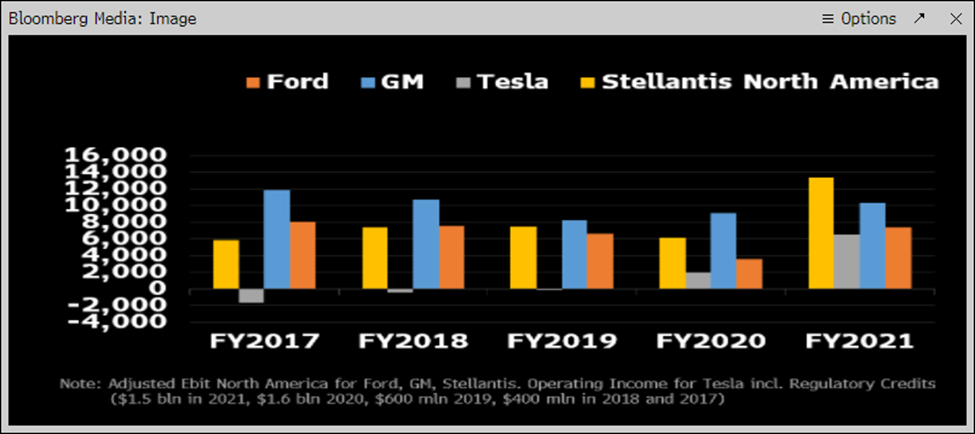

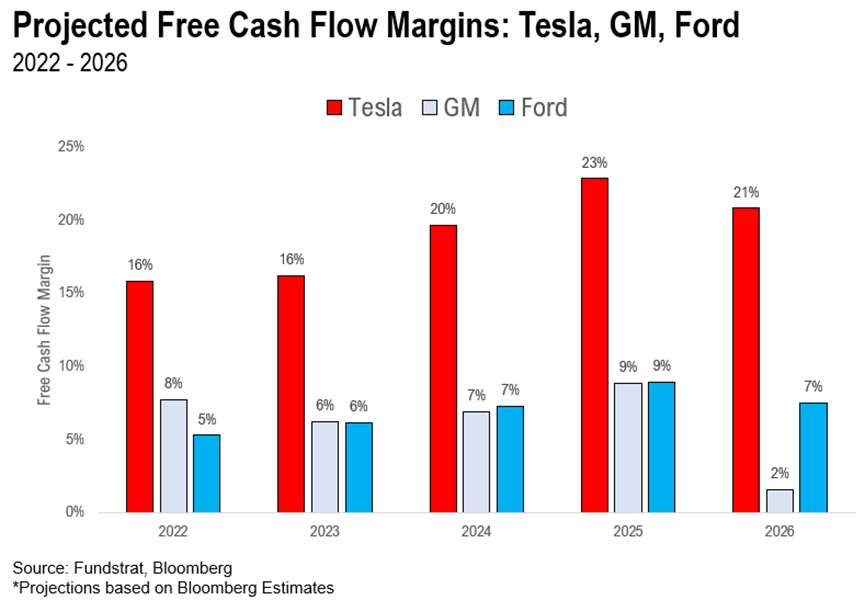

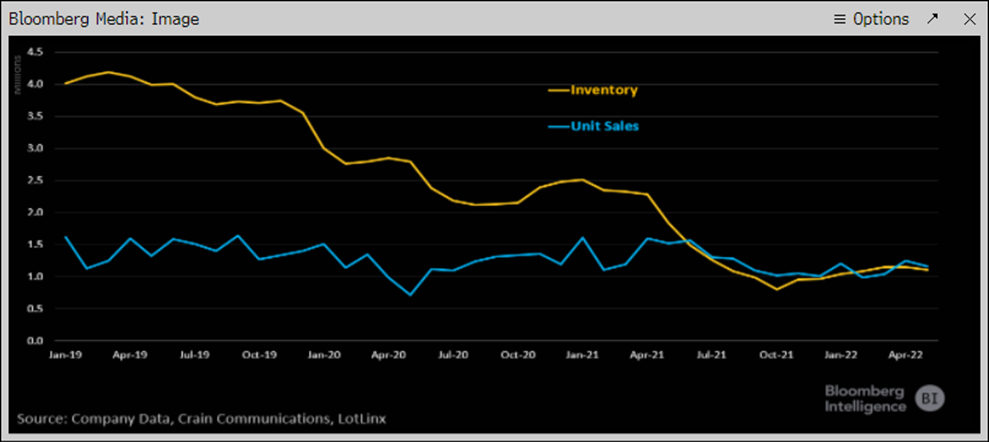

The legacy automakers rely on internal combustion vehicles for the bulk of their profitability. US consumers particularly seek the trucks that GM and Ford specialize in. These contributed a whopping 82% of the US retail revenue in the first quarter of 2022. GM, Ford, and Stellantis have essentially been building their capacity for electric vehicles. Still, those efforts have may seem even more urgent after the new California ban on selling new gas-powered vehicles by 2035. At the same time, Tesla continues to enjoy a vast valuation premium. It is worth mentioning that Electric vehicles only made up about 7% of sales in the same quarter, and ¾ of that revenue went to Tesla. The pure player, which remains dominant in EV sales, also accounted for about the same ratio of total EV volume in 2021, at 72%.

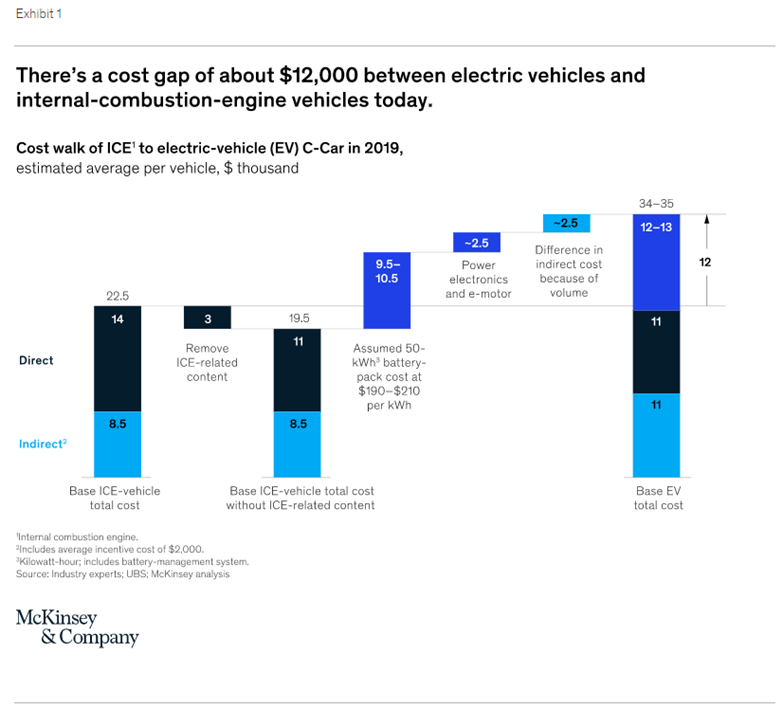

The industry is at a major crossroads. Until recently, Tesla dominated EV sales and acquired quite a lead in manufacturing them profitably. Now the legacy automakers are starting to roll their EVs off the assembly line. Ford has beaten other EV truck offerings to the market with a significant lead time. Newer pure-play EVs like Lucid and Rivian are in the early stages. Still, their efforts to achieve competitive scale and output with the more established guys (which now includes Tesla) will be dramatically complicated by the rise in materials costs, which affect the critical input price of resource-rich batteries required for EVs. Unfortunately, at the same time, price pressures have gone up for EV makers due to commodity interruptions from Ukraine, squeezing already tight margins on EVs; the pressure to adopt them quicker has gone up with recent trends in state law, as we’ll discuss below. So, the legacy automakers may be tempted to dither on some of their EV plans as the profitability of internal combustion vehicles is now even more relatively appealing.

Tesla’s recent surge in profitability and massive expansion of production output enable it to take advantage of scale better than new entrants. All else being equal, the price rises also raise the barrier to entry for newer players like Rivian and Lucid Motors. The legacies should be able to outproduce them, and commodity costs will set back their efforts to achieve scale. However, Tesla’s dominance is being most heartily challenged by Jim Farley at the helm of Ford. They are the only automaker with scale to have produced a full-size battery-only pick-up truck for mass consumption. The F-150 is one of the most successful products in American history, and Ford should have a lead of at least a year before GM and Tesla can directly compete with this product. It may be able to crucially expand the number of customers willing to buy EVs past the markets typically served by Tesla’s business model which tends to serve more affluent customers and be less dependent on credit. Ford’s massive credit arm and dealer infrastructure ensure it has the means to exploit this advantage.

Future Drivers and Catalysts That Will Define The Next Chapter of Mobility

“Build a sports car, use that money to build an affordable car, use that money to build an even more affordable car. While doing the above, also provide zero emission electric power generation options.” – Elon Musk, From the Secret Tesla Motors Master Plan Just Between You and Me

We haven’t talked too much about Mr. Musk yet. We know he’s controversial. Some might say he’s a “Mad King” and others would postulate that he can do no wrong. Of course, the truth is probably somewhere in between. We would suggest that Musk’s achievements in the auto industry are akin to Napoleon Bonaparte’s achievements: he was an outsider viewed as having no shot that shook the foundations of the establishment to their very core. Remember though, even Napoleon himself fought 60 battles and lost 7 of them. Even the very best are not immune from defeat. Dilly dallying and messing around on issues most CEOs would stay far away from certainly won’t help one’s staying power either. Ultimately, a CEO’s moral duty is to their shareholders, workers and customers and all distractions from that duty are likely not appreciated by many stakeholders. Nonetheless, despite the fact the legacies produce a lot more cars, there’s a reason Tesla’s valuation is higher.

Time and time again, Mr. Musk has set the tempo his competition follows and the future of mobility will largely be defined by the breathtaking achievements of him and his team. Whereas the stodgy halls of Chrysler, GM and Ford leadership became decidedly detached from the core function of their companies and the people doing much of the work on the front-end, Musk empowered engineers, moved quickly and nimbly, and in doing so has taken what some characterize as an insurmountable lead in electric vehicles.

However, one lesson from the past is that major leads can evaporate in the auto industry quicker than most people would think. Between 1997 and 2000 Ford seemed like it was back. It earned, at the time, the prodigious amount of $39 billion over that period. Its new CEO was promising to modernize the firm and bring it into the internet age. Then, it burned all its advantages and plunged into one of its darkest periods ever. Musk and Tesla’s leadership appear to be doing what Ford did not, investing their money wisely. Tesla’s quote above was from 2006, and the company hasn’t strayed from that plan.

Detroit’s woes were caused by short-termism and “too much hat, not enough cattle” as they say in Texas. Nasser would make big promises and rattle off buzz words, and then he would set up show rooms with the premier brands they had bought up front and their core products hidden in the back by the coffee. They lost the dream and the intent of the great commercial revolution their forebears had unleashed. Tesla has its own flaws and if you’ve tried to get yours repaired when it breaks you know it can be a real expensive hassle. But they have undoubtedly set the tempo their competitors are now marching to. We appropriately titled our last SFN on Tesla as “The Beginning of a Dynasty.” Now, we’ll close with a discussion of recent catalysts and how they may affect the market.

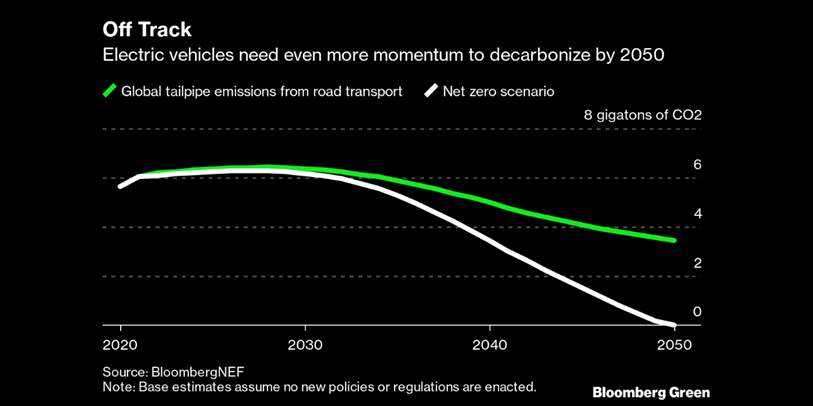

- Emissions Regulations and Government Concern About Climate Change

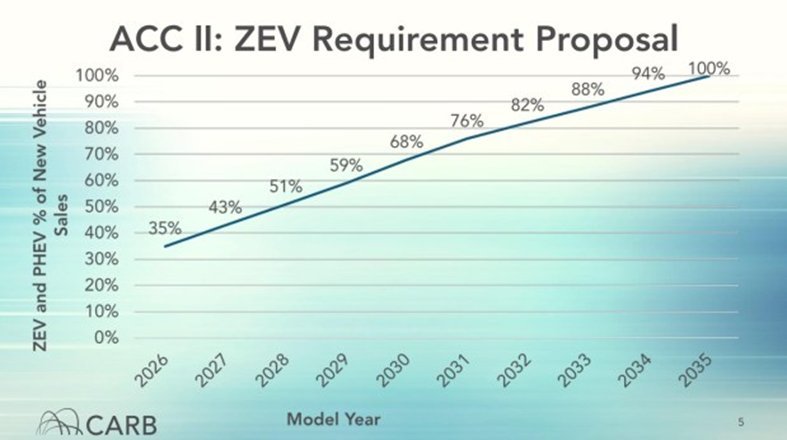

Recently, the state of California announced it will ban the sale of new gas-powered vehicles by 2035. This has special significance because since California regulated emissions before the Federal government did, their regulations are not pre-empted by Federal law like most states. Many European countries have passed similar laws urging this same goal by 2030, but California’s will likely lead to much of the more left-leaning states adopting the same rule, since they can opt to adopt the largest state’s rules in favor of Federal standards. Ultimately, this could result in most of the US population, or close to it depending on demographic trends, being unable to purchase new gas-powered models in 13 years.

Critics have noted that California’s power infrastructure needs a lot more modernization and re-jiggering to support such a goal. It is already heavily constrained and needs to be reformed in many cases because of the risk from wildfires. California Governor Gavin Newsom is pushing to keep some nuclear plants open and supports bills to expand infrastructure, but as Honda noted even though they agreed with the impetus of the rule, it is very ambitious in terms of domestic infrastructure capabilities that currently exist. However, the intransigence of automakers on climate has long-since passed. Ford, VW, BMW, Honda and Volvo already made voluntary agreements with the state to limit their emissions. The other issue is that because of recently rising raw materials cost, the time when profit parity with gas-powered vehicles is achieved has likely been pushed back by years. All and all, the auto industry seems prepared for this eventuality and had already committed full tilt to going electric, but whether the law is implemented and the infrastructure to support it built is still up in the air.

- Rising Raw Material Costs

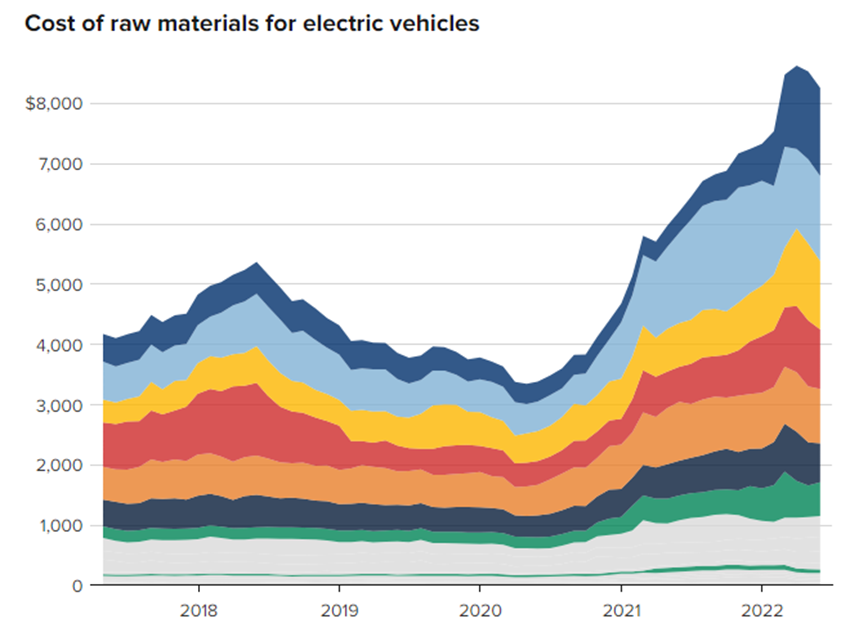

The commodity interruption from the War in Ukraine is usually dominated by discussions about Energy, but the industrial metals necessary for EV production are victims as well. The increase in vital inputs like cobalt, lithium and nickel has been very pronounced. According to a report by Alix partners raw materials costs have more than doubled. This effects both the legacy automakers with their ambitious expansion plans, and also pure-plays like Tesla, Rivian and Lucid. The margins on EVs are thinner than on ICE, so this squeezes profitability to the point where prices have to be significantly raised.

The raw materials costs have also gone up for regular cars, but their margins are higher. And the legacy makers like GM and Ford have cleared out production of unprofitable models to help them fund their ambitious and necessary forays into electric. All and all, this may complicate the realization of those plans. Stretching out when profit parity will occur right as emissions restrictions are banning the sale of their profit drivers should be one of those tricky, drama-filled times that pepper the history of this iconic industry. All and all, Tesla is the best positioned. The new EV entrants trying to nip at its heels will now have a harder time scaling production when Tesla has already gotten there. This only makes Tesla’s lead in EVs more entrenched, particularly since they have a more affluent customer base that will be more willing to incur the costs. Tesla’s greatest threat likely comes from Apple, but we’ll need to learn more as it is revealed before definitively saying so.

- Geopolitical Risk and Receding Globalization

There are very few industries that are as globalized as the auto industry. Tesla even has major production facilities in China. There is a major trend toward hardening supply chains and trying to cut out the middleman for materials. EV makers are realizing what time it is and trying go straight to the source. Elon Musk, for instance recently met with the President of Indonesia to discuss potential investments. Ford has been making deals to accelerate their push into EVs as well. Mary Barra at GM also locked in a long-term supply contract with Livent. The auto companies are poster-children of the “just-in-time” supply chain. If geopolitical conditions continue to be persistent and acute, that way of doing business could be a thing of the past. For companies like Ford and GM with massive international footprints, the tide of moving labor and production out of America might move in the other direction. Only time will tell.

The auto industry has just started recovering from the supply chain woes of the COVID era. Recent geopolitical tensions around Taiwan would be a major wrench in the global economy and particularly technology. It would also make the semi-conductor shortage the auto industry recently experienced seem like child’s play. It will be difficult to determine just how much re-tinkering of supply chains will be necessary. Hopefully, the geopolitical situation reverts toward one of global cooperation rather than continued acrimony and conflict. However, the auto industry will be one of the primary victims if it does not. This is a major risk for the industry. Overall, one thing benefitting the auto industry is that demand is persistent, and supply is low. Luckily, this supply environment does help to mitigate the above risks we just discussed.

So, what does this all mean and which auto stocks should you buy? Well, this is focusing on the industry but we actually don’t think that right now is necessarily the best time to buy auto stocks. Tesla may undergo further multiple pressure if rates go up and stay elevated and the cyclical nature of the legacy guys mean they will likely be subject to some downward earnings revisions. Please keep an eye out because we will be releasing a special chart-book and financial analysis of our favorite auto stocks and good levels, based on valuation to serve as potential entry points if you’re interested in the sector. Keep your eyes peeled and thank you for reading!