Special Edition: Everything You Need to Know About Jackson Hole

The Jackson Hole Symposium has become one of the pre-eminent events for central bankers, policymakers, and economists. The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City hosts the event every year. Each year has a different theme. This year’s theme was “Reassessing Constraints on the Economy and Policy. The agenda for the event can be found here. The event was first held in 1982 in the period immediately after Volcker’s controversial actions to break the back of inflation. Then Kansas City Fed President Roger Guffey shrewdly put the event in Jackson Hole to entice Chairman Paul Volcker’s attendance. Volcker was a flyfishing enthusiast and Wyoming is a great place for that activity. Hence, one of the world’s most important events for central bankers and economists was inaugurated. The first theme of the symposium was “Monetary Policy Issues in the 1980s.”

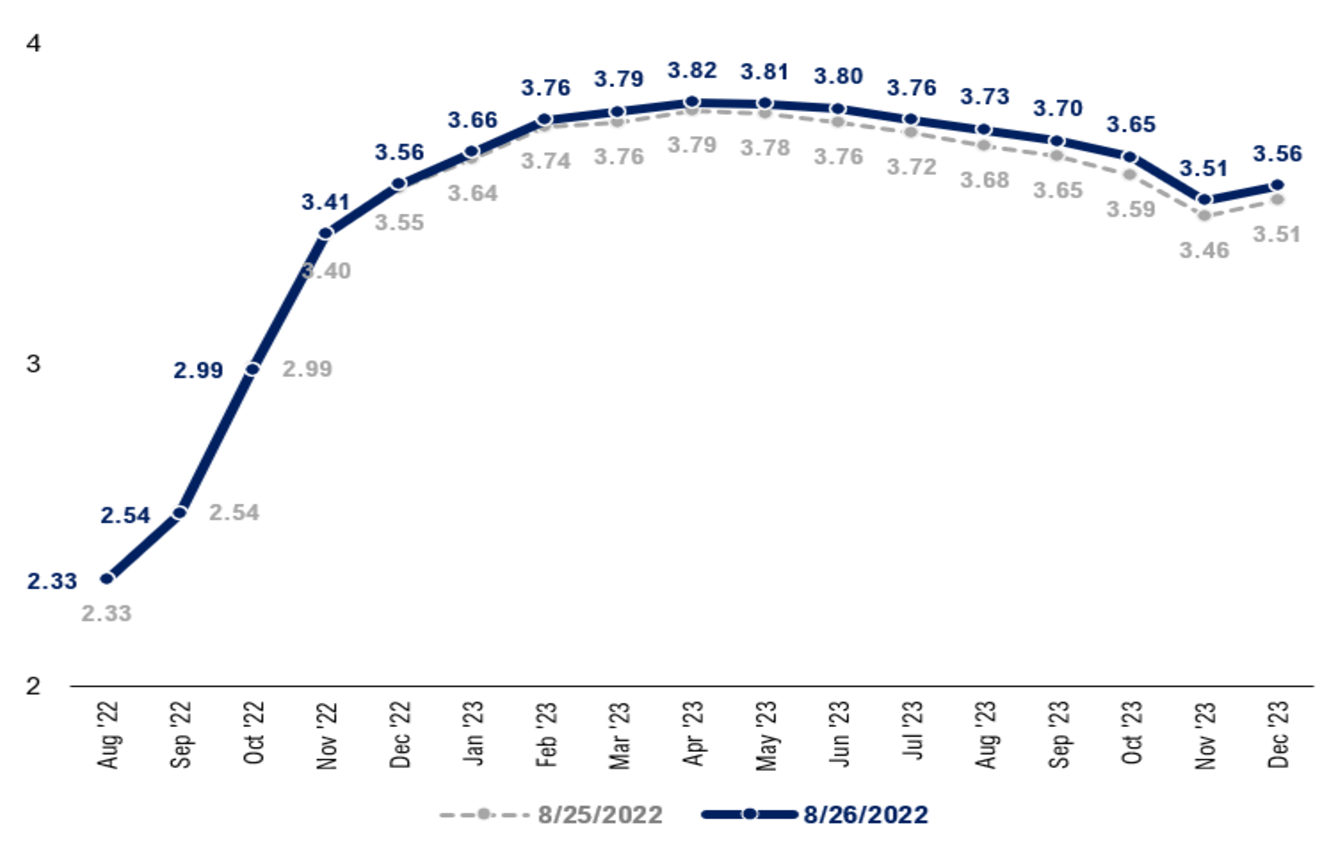

Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell made his much-anticipated keynote speech at the Fed’s annual Jackson Hole symposium. While fixed income markets were largely positioned in anticipation of a hawkish message, equity markets retreated significantly, with the losses being the worst in high P/E equities. Powell had an abbreviated speech and there was very little for the doves to hang on to. Most of the commentary from Fed governors suggested Powell wouldn’t waiver and would focus on the seriousness of the inflation fight despite a recent “welcome” pullback in the inflation data. The initial response in the Fed Futures market was to price in a higher rate, but the changes weren’t major as you can see below.

We wanted to give you a special report on where markets stand in the wake of Powell’s impactful speech. First, let’s discuss some of the key takeaways from his keynote this morning.

- The Fed views inflation expectations becoming unanchored as a far more serious risk than the ancillary effects (on economic growth) of their tightening efforts. In an unusual occurrence, Fed Chairman Powell acknowledged that the Fed’s efforts to rein in inflation may cause some “pain” for American households. For instance, he mentioned the labor market was out of balance and that unemployment would likely need to move higher because of the Fed raising rates. Since concerns about inflation trump concerns about growth, the Fed can be expected to continue raising even though we are near what many economists think is the neutral rate (i.e., the rate at which Fed Funds is having neither a restrictive nor accommodative effect on the wider economy). Doves had been holding out hope that the Fed might pivot as tightening financial conditions made their way through the economy. Powell dismissed this notion. Powell specifically mentioned there will be “some pain to households and businesses,” which he described as unfortunate but necessary.

- The Fed needs to see much more data showing cooling inflation before it will switch to an accommodative posture. After the last 75 bps, the rate should be near neutral. However, with inflation at over 4 times the Fed’s 2% target, as Powell mentioned, there will need to be at least a few quarters worth of data showing strong evidence that inflation is indeed moving toward the Fed’s target. This is also complicated by the fact that a lot of the inflation drivers are on the supply-side, meaning that the Fed’s efforts to rein in inflation (which occurs by tightening financial conditions and slowing demand) won’t even have the intended effect. Minnesota Fed President Neel Kashkari recently estimated that about 2/3 of the inflationary pressure comes from the supply side, things like energy price spikes from the war and bungled COVID-19 supply chains, rather than persistent consumer demand. The Fed’s main policy can affect the latter but not the former.

- The market got the Fed’s message on Friday. Powell’s speech was very short, only 10 minutes. However, there was room for a key Chairman Volcker quote and that wasn’t an uncalculated decision. In the wake of Powell’s comments last time, financial conditions significantly eased. If the market thought Powell was bluffing about keeping rates higher for longer, which is a main takeaway of his speech, then they didn’t show it. Rates rose, and long-duration stocks led the losses. Remember, the Fed raising rates affects equities since the risk-free rate is used to discount future earnings. So, both these effects show that the market took Powell at his word, at least for now. Even Larry Summers, often a critic of Powell, said that the Chairman did what he needed to do on Friday.

What Does Powell’s Speech Say About the Upcoming Meeting in September? 50 bps or 75 bps?

Jackson Hole is not a regular FOMC policy meeting, so policy is telegraphed from this event, but it is not directly made. The next Fed meeting where policy is set is September 20-21. The question now is whether the FOMC will raise by 50 bps or 75 bps at their next meeting. Commentary from Fed officials has been varied on this, but one of the two is almost certain after Powell “didn’t blink” on inflation, as one prominent Fed Watcher suggested. The Fed Funds Futures curve implies that 75 bps is slightly favored after his hawkish speech.

We concur with this conclusion, and unless there are major developments between now and then, we’d say 75 bps is more likely. We think Bullard put it well in his Jackson Hole appearance when he said that he favors front-loading the hikes because “we have inflation right now, we have a strong labor market right now.” His colleagues were less certain: Bostic, George and Harker essentially said they would wait to see the August data before deciding but all stressed the centrality of vanquishing inflation over other concerns, in line with Powell. The Fed has raised rates 85 times since 1983. Over 85% of the time, those rate increases were less than 50 bps. So, markets are inferring that the Fed will make a historically large hike in September, whether it is 50 bps or 75 bps.

What Data and Catalysts Could Play a Role in the Fed’s Thinking Between Now and September?

Economic data show the economy has been slowing, but there is also reason for conflicting interpretations of that data to create obscurity and uncertainty in the market. For example, Gross Domestic Product measurements have shown contraction two quarters in a row. Recent Gross Domestic Income, however, shows that growth continued this quarter. Consumers in the lower income quintiles have shown some signs that they are under pressure, but affluent consumers are maintaining strong levels of spending. Then, of course there are several pressures from major macro risks:

- The War in Ukraine: This is a major economic issue because of the interruption in various commodity markets but especially in energy markets. Recent relief in inflation numbers was largely driven by declining energy prices. They had initially spiked to high levels after the beginning of the war in Ukraine but have since subsided, giving consumers some relief. Energy is particularly important because it is not just the price of the energy itself that is affected by high costs. In the United States, transporting food is one of the biggest components of the overall cost. As goes energy, so goes inflation. Concern has been mounting that Russia may cease all energy exports to Europe as winter approaches to gain leverage and shake Western unity. If the worst case happens, energy could see renewed price pressures.

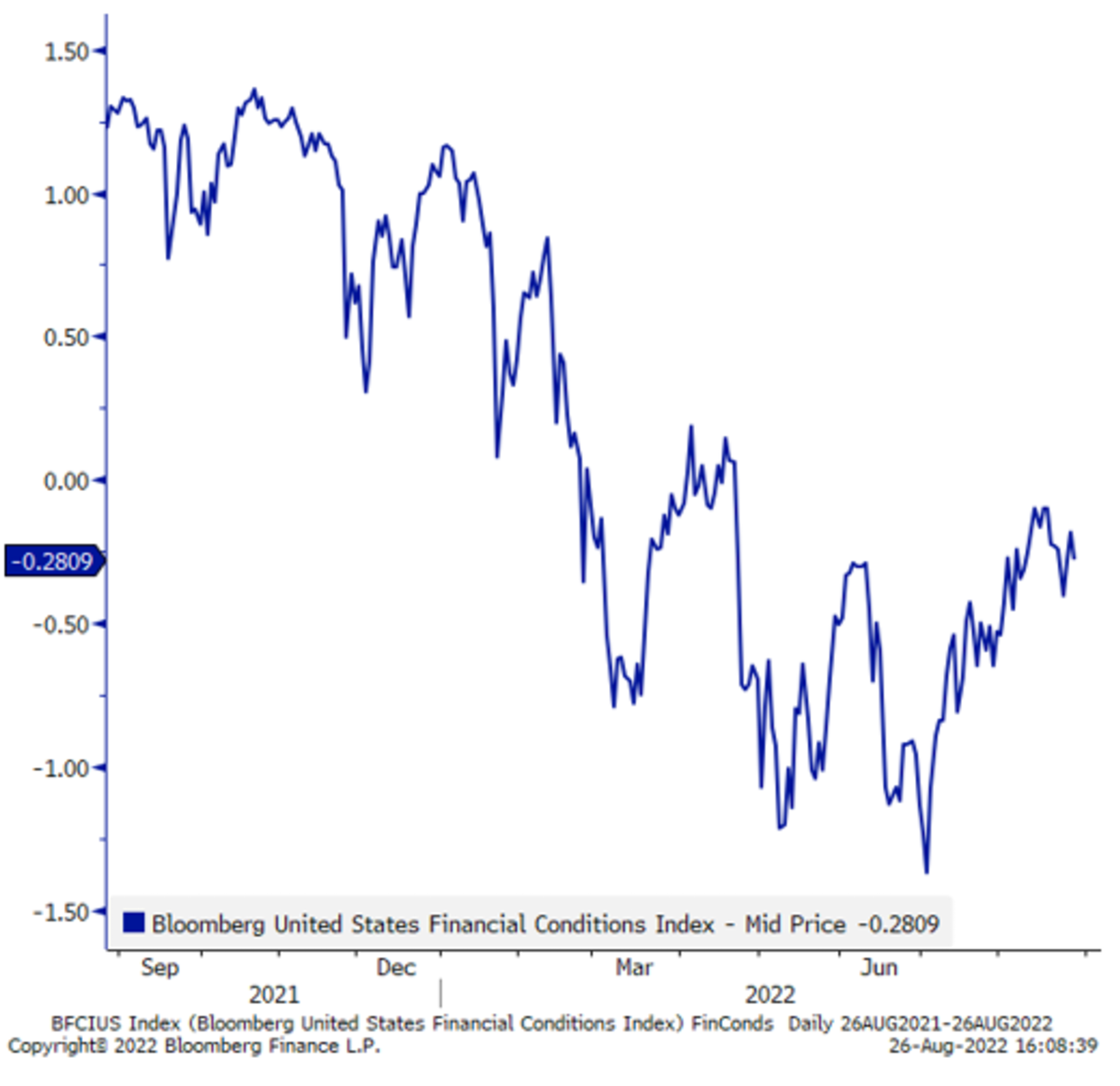

- Financial Stability and Growth: Financial conditions have eased in the run-up to Jackson Hole, so ironically optimism about a potential dovish pivot makes it less likely one will happen. The Fed has clearly messaged that its primary concern right now is inflation and, given the extraordinary levels of CPI which are still at multi-decade highs, it seems it would take a very serious breakdown in financial stability to get the Fed’s eye off solving inflation. If such an event were to occur, markets would likely drop a significant amount before the Fed would indeed pivot. We think it would take an awful lot for the Fed to become transfixed on growth and financial stability over inflation at the current levels. Of course, a rapid drop in inflation could make these concerns come more to the fore. In the event this does happen, Powell’s speech likely gave him a bit of breathing room.

3. Inflation Data: One of the terms that is regularly swirling around Fed-centered discourse is “data-dependent.” This is the idea that the Fed will let the incoming data drive its decision-making and that it isn’t dedicated to one way or the other. There is still a certain element of this in the decision-making process, as evidenced by Harker’s, Bostic’s and George’s comments at Jackson Hole preceding Powell’s. However, the message from Powell’s keynote is clearly that the threshold for accommodative policy is a lot higher than some market participants had been suggesting. Our Head of Research, Tom Lee, has been at the forefront of analyzing soft data (which is more leading than hard prints). We have a lot of evidence that inflation has peaked and that certain core drivers will go from major contributors to price pressures to becoming outright deflationary. Travel spending and used cars are examples. If the leading data we are analyzing starts manifesting itself in the hard data quickly, the Fed could change its tune a bit. Generally, we see a soft landing as more likely than consensus. Also, keep in mind that a strong dollar helps the Fed’s tightening efforts as well.

4. The US Consumer: The US consumer has taken it on the chin and is still standing. Yes, there have been some major setbacks and energy prices put pressure on the wallet, but the dire forecasts about a collapse in demand have not come true. There has been an orderly and manageable slowdown in economic activity but nothing that makes you want to “hide under your desk” quite yet. Credit performance on the consumer side has not shown major distress yet and levels of credit utilization suggest consumers can still tap unused sources to fuel consumption. Housing has been dinged by Fed Policy, but in some ways, this is a good thing. The fact that housing is cooling and responding to rate hikes, rather than not responding as it did during the Global Savings Glut, is probably viewed as a positive by the Fed.

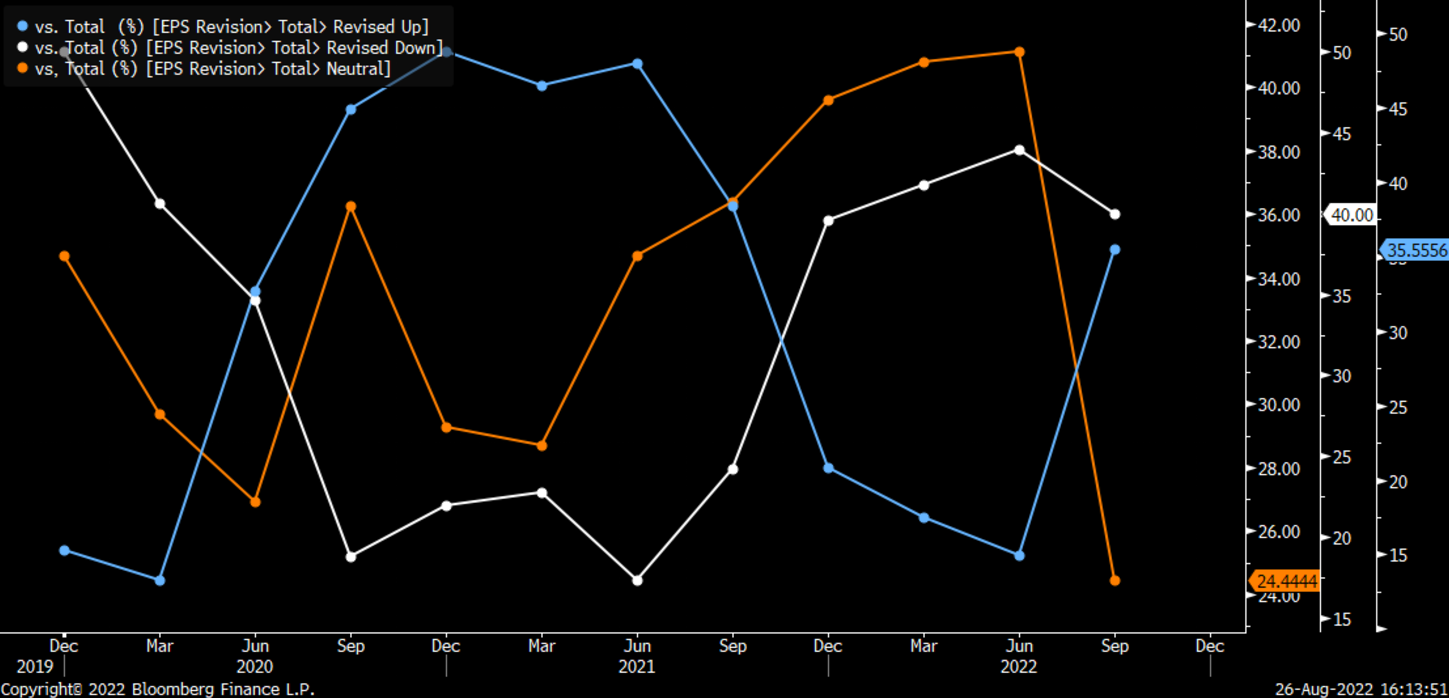

5. Earnings: Slowing economic activity means slowing or declining earnings for many companies. Without the tailwinds for P/E expansion caused by accommodative Fed policy, some have suggested that stocks only can go one way. Traditionally, Fed tightening cycles have been bad for stocks. However, earnings numbers this quarter didn’t turn out to be as bad as feared and based on price reactions they seemed to be more expected than last quarter. It is true that without energy, a sector enjoying a profits boom, we are in an earnings recession. However, positive guidance significantly increased this quarter for the S&P 500, as shown above. The verdict is likely still out on whether we see a prolonged and deep earnings recession, or whether the economic slowing is mild enough for companies to maintain margin expansion. According to BEA data yesterday, non-financial company margins reached a high not seen since 1950, so for the time being companies appear able to pass on rising costs to the consumer at an aggregate level, despite some notable exceptions. Revenue guidance has been flat, but momentum for EPS guidance has turned positive. Again, though, there could still be A LOT OF earnings pain ahead. Whether or not the market can see through it will likely depend on whether inflation is persistent or whether it has begun a precipitous decline, as the soft data we’re looking at suggests.